Social, economic, and cultural factors are undeniably crucial in shaping our health and life trajectories. However, the intricate interplay between these societal influences and our biology often remains a mystery. This article delves into the concept of biological programming in health and social care, exploring how our early experiences, deeply rooted in social contexts, can fundamentally alter our biology and have lasting impacts on our well-being throughout life.

Understanding the Biosocial Interplay: Weaving Together Biology and Society

The term “biosocial” signifies the dynamic and reciprocal relationship between our biology and our social environment. It’s not a one-way street where society merely impacts biology, or vice versa. Instead, it’s a continuous, two-way interaction. Our social experiences, from our families and communities to broader societal structures, constantly interact with our biological systems, shaping our development from the earliest stages of life.

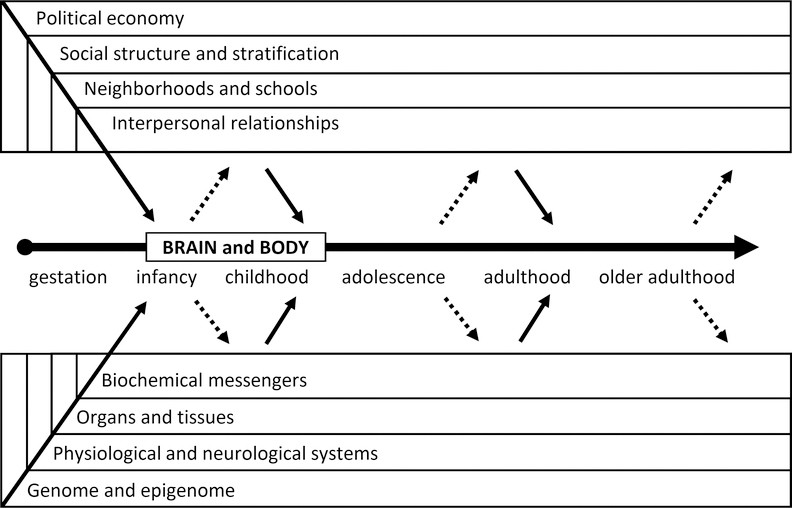

Figure 1 illustrates this complex biosocial dynamic, depicting the nested layers of social contexts “outside” the body influencing our developing brains and bodies across our lifespan. Simultaneously, it portrays the interacting levels of biological organization “inside” us, responding to and shaping our social worlds. Biology here encompasses everything within us that contributes to growth, reproduction, and maintenance, from our genes to our organ systems.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model illustrating the bidirectional relationship between social contexts and biological organization throughout the human life course.

Social factors are equally multifaceted, encompassing our relationships, interactions within groups, and the shared norms and institutions that structure our lives. This also includes physical environments shaped by social relations, such as exposure to pollutants or access to recreational spaces.

A biosocial perspective, therefore, bridges the gap between biological, medical, behavioral, and social sciences. It acknowledges that biology and society are intertwined forces, and understanding one without the other provides an incomplete picture of human development, behavior, and health. This transdisciplinary approach is crucial for researchers across various fields like anthropology, psychology, epidemiology, sociology, and medicine, all striving to unravel the complexities of human well-being.

Biological Programming: Early Experiences Sculpting Lifelong Health

Why should we, especially in health and social care, focus on biology? While social and economic outcomes are undeniably shaped by social factors, understanding the underlying biological mechanisms provides crucial insights. Biological programming, also known as developmental programming or biological embedding, offers a powerful framework to understand how early life experiences, particularly those shaped by social contexts, can alter our biological pathways and predispose us to certain health and social outcomes later in life.

Humans are fundamentally biological beings deeply embedded within social structures. Our biology is not isolated; it’s profoundly influenced by our social environment. This is strikingly evident in human health, where “social determinants of health” – factors like socioeconomic status, education, and social support – are widely recognized as powerful influences. Biological programming illuminates the pathways through which these social determinants leave a lasting imprint on our physiology, shaping our vulnerability or resilience to disease.

Context is paramount to human biology across different timescales. In the short term, our bodies employ processes like homeostasis and allostasis to adapt to immediate environmental changes. For instance, encountering a perceived threat triggers cortisol release, preparing our body to respond to stress. Once the threat subsides, cortisol levels typically return to normal. However, chronic exposure to adverse social conditions can disrupt these regulatory systems, leading to physiological “wear and tear.” Lower socioeconomic status, often a source of chronic stress, is linked to altered cortisol patterns, contributing to long-term health risks.

Biological programming extends beyond short-term adaptations. Crucially, early life experiences during critical or sensitive periods of development can have disproportionate and enduring effects on our biological structure and function. For example, individuals born with lower birth weight, often linked to socioeconomic disadvantage, may exhibit elevated cortisol levels in adulthood. This points to a biological mechanism through which social inequality can be biologically embedded, impacting health across generations.

By delving “under the skin” through biological measures, we gain objective insights into pre-disease pathways, even before clinical symptoms manifest. Tracking biological markers like blood pressure from childhood reveals individuals at higher risk of future cardiovascular disease, even in the absence of current hypertension. Biological programming helps us understand how social environments influence these early disease pathways, offering opportunities for preventative interventions.

Understanding biological programming also allows us to identify the specific aspects of social and physical environments that are most detrimental to health and well-being, as well as protective factors that promote resilience. The concept of “embodiment” highlights how our bodies literally and figuratively tell stories about the quality of our social environments. Biological measures can reveal these narratives, reflecting the impact of social contexts on our physical selves.

Furthermore, while social factors profoundly impact biology, the reverse is equally true. Biological factors, shaped through biological programming, can also influence our life trajectories and social attainments. For instance, lower birth weight can negatively affect cognitive development and educational attainment, impacting social mobility. Ignoring these biological influences can lead to incomplete or biased models in social science research.

Recognizing biological programming is also vital for translating social science research into effective policy. Biological measures can serve as objective indicators of the quality of social conditions, motivating interventions to prevent disease rather than just treating it. For example, lead screening in children can inform housing policies aimed at reducing lead exposure, preventing costly cognitive and behavioral disorders. Similarly, understanding the biological impact of social relationships emphasizes the need to integrate social connection assessments into routine health screenings.

Socializing Biology: Recognizing the Social Roots of Biological Processes

While the biosocial approach is increasingly embraced within social sciences, it’s equally crucial to “socialize” biology itself. Traditional biological research often prioritizes explanations “inside the body,” focusing on cellular and molecular processes while overlooking the powerful influence of social contexts “outside.” The sequencing of the human genome, while groundbreaking, risks overemphasizing genetic determinism and neglecting the crucial role of environment.

However, social scientists have long documented the profound impact of social contexts on human development, physiology, and health. From early anthropological studies demonstrating the malleability of physical traits in response to environment to decades of research highlighting the health impact of social relationships and socioeconomic status, the evidence is clear: human biology is deeply social.

Biological programming underscores this point. It highlights that our biology is not predetermined but actively shaped by our social experiences. Biosocial research, conducted in real-world community settings, shifts the perspective in biological sciences. It reframes human biology, development, and health as complexly determined by both internal and external forces, with social contexts playing a potentially pivotal role in shaping our physiological functions and overall health.

This perspective aligns with developmental and social/behavioral sciences, which have long emphasized the intricate interplay of genes, biology, and society throughout life. With increasingly sophisticated tools for integrating biological measures into social science research, we are poised for a new era of biosocial scholarship. This will enrich both biological and social sciences, fostering stronger collaborations and a more holistic understanding of human well-being.

Methodological Innovations: Bridging the Gap Between Social and Biological Research

Historically, social science research relied heavily on surveys and vital records, offering broad population-level insights but limited biological depth. Conversely, biomedical research employed in-depth biological measures in controlled settings, often lacking generalizability and overlooking social context.

However, the past decade has witnessed a methodological revolution, bridging this gap. Low-cost, field-friendly methods for collecting biological samples like blood, saliva, and urine in homes and communities have emerged. Advancements in assay technology enable high-resolution measurement of proteins, genes, and epigenetic markers from small samples at lower costs. Portable devices now facilitate convenient monitoring of sleep, physical activity, blood pressure, and body composition.

These innovations have spurred the integration of objective biological measures into large-scale social science surveys. Dried blood spots and saliva samples are now routinely collected in major longitudinal studies, providing a wealth of biological data alongside rich social and behavioral information.

This integration of objective biological measures is revolutionizing our understanding of biological programming. It allows us to directly investigate how social, economic, and community factors shape human biology and health, and vice versa. By bringing biological data collection into real-world settings, we capture a wider range of environmental variation, highlighting the crucial role of context in shaping biological processes. These methodological advancements are not only enhancing our understanding of biological programming but also fostering collaborations between social, life, and biomedical scientists, paving the way for groundbreaking discoveries about human development and health.

The Life Course Perspective: Unfolding Biological Programming Over Time

Human development is a lifelong journey shaped by both social and biological forces, with intergenerational connections starting in the womb. While it’s widely acknowledged that early life conditions are crucial, much research overlooks how developmental processes are interconnected across life stages and the dynamic interplay of social and biological factors over time. This gap stems partly from a lack of longitudinal, life course data and intergenerational study designs, and partly from disciplinary silos that focus on isolated determinants of health or social outcomes at single time points.

A life course perspective is essential for understanding biological programming because our health and well-being at any point in time reflect the cumulative impact of prior social-biological interactions throughout our development. Life phases and social roles are often intertwined with biological events. For example, puberty marks biological maturation, while societal norms dictate when individuals transition to parenthood. Biological programming, therefore, unfolds across the life course, shaped by the continuous interaction of biological and social forces. Understanding this requires assessing both biological and social features throughout development, across generations, to gain a complete picture of human well-being.

Biological Programming Across Life Stages

Within social and behavioral sciences, aging research has been a pioneer in biosocial approaches, recognizing aging as a process shaped by both internal and external forces. However, even aging research has often lacked a strong life course perspective, primarily using cross-sectional designs and focusing on older adulthood.

While cross-sectional studies have been valuable in documenting social gradients in health and mortality in aging populations, they offer limited insight into the biological programming processes that unfold earlier in life and contribute to these disparities. The advent of longitudinal aging studies has allowed researchers to examine how earlier life conditions relate to health outcomes in older age. Furthermore, incorporating objective biological measures into these longitudinal studies has enhanced our ability to understand the biological mechanisms underlying aging and disease.

However, even longitudinal aging studies typically begin in mid-life, missing crucial earlier life stages where biological programming is most active. To address this, researchers are increasingly incorporating retrospective data on early life conditions into aging studies, providing a more complete life course perspective.

Research on the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) has also gained significant momentum, highlighting the profound impact of early life exposures, including prenatal and childhood nutrition, on later disease risk. This research underscores the long-arm of childhood, demonstrating how early life circumstances, shaped by social factors, can have lasting consequences for health decades later.

However, much of this DOHaD research focuses on linking early life conditions to later disease outcomes, often with cross-sectional designs, overlooking the intervening periods of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. To fully understand biological programming, we need to examine the social processes and contexts that shape biology across the entire life course.

Adolescence and the transition to adulthood are particularly critical periods. During these stages, individuals begin to make independent choices about their environments, health behaviors, and lifestyles. These choices can either reinforce or alter the biological pathways established through earlier biological programming. Adolescence is also marked by profound biological and neurological changes associated with puberty, further shaping brain development and behavior. Understanding biological programming requires considering the contributions of these dynamic developmental stages.

Adulthood brings its own set of social and biological challenges. While neurological development may slow, adults face new stressors related to relationships, work, and family. Stress processes, as exemplified by cortisol, are key biological mechanisms through which social environments impact health throughout adulthood. Middle adulthood, while potentially offering greater stability, can also be a period of intense social demands and stressors, particularly for disadvantaged populations.

Each life stage presents unique social and biological forces that shape lifelong development and contribute to both well-being and social inequities. Biosocial research, informed by a life course perspective, is crucial for unraveling how biological programming unfolds across these stages, linking early experiences to later health and social outcomes. Moving beyond cross-sectional designs to uncover the underlying life course processes is essential for developing effective interventions and promoting health equity.

Biosocial Life Course Models: Understanding Social Gradients in Health

Two primary life course orientations guide biosocial research on health and social inequality. The first examines how social stratification across the life course contributes to later health outcomes. This orientation builds upon the vast literature on social determinants of health, but adopts a life course lens to understand how social disadvantage becomes biologically embedded over time through biological programming.

Social stratification, encompassing both intergenerational and intragenerational processes, shapes access to resources and opportunities across the life course. Understanding how these social exposures, both positive and negative, “get under the skin” to influence health through biological programming is central to this biosocial approach.

Ideally, social stratification is measured longitudinally, as a dynamic life course process. Social exposures, such as supportive parenting or childhood poverty, accumulate over time, creating unique social stratification trajectories for each individual. Biological outcomes are then viewed as consequences of these trajectories, reflecting the cumulative impact of social experience on biological programming.

The stress response framework is a prominent paradigm for explaining how social inequalities are linked to biological dysregulation and health outcomes. Chronic or intense social adversity leads to chronic stress, which in turn disrupts biological systems, contributing to poor health. However, the timing of social exposures across the life course can differentially affect biological mechanisms and health outcomes.

Figure 2 illustrates different life course models explaining how social disadvantage can impact later health.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of three life course models illustrating the impact of social disadvantage trajectories on health outcomes.

The “sensitive period” model highlights that exposures during specific developmental windows have stronger and more enduring effects on health due to biological programming. These early exposures can induce biological embedding, leading to lasting structural and functional changes that are difficult to reverse. The impact of these sensitive period exposures may remain latent, manifesting in health outcomes decades later.

The “accumulation” model emphasizes the cumulative effect of persistent advantage or disadvantage across the life course. Multiple exposures, whether recurrent stressors or different adverse experiences, additively and synergistically impact biological mechanisms and health. For example, prolonged poverty across childhood and adulthood has more detrimental health consequences than poverty experienced only in childhood.

The “pathway” model, also known as the “chains of risk” model, emphasizes how early social exposures can set individuals on trajectories that increase their risk of subsequent exposures. Early disadvantage can create a chain of events, leading to further social and biological risks. For example, early life socioeconomic status can shape adult socioeconomic status, which in turn is a more direct predictor of adult health.

The second life course orientation examines the reverse pathway: how biology and health influence social stratification processes. In this view, biological factors and health trajectories, shaped by biological programming, become important determinants of socioeconomic outcomes. For example, childhood health can significantly impact educational attainment, labor force participation, and income in adulthood.

Figure 3 illustrates how early life health can influence later socioeconomic status.

Figure 3:

Conceptual diagram illustrating the role of health, shaped by biological programming, in influencing social stratification processes.

Research has shown that obesity during adolescence, a condition with biological and social roots influenced by biological programming, can have lasting negative impacts on education, employment, and social status in adulthood. Chronic health conditions in youth can also disrupt educational and career trajectories.

Understanding how biological processes, shaped by biological programming, contribute to social stratification is crucial for identifying when and how biomedical and social interventions can be most effective in reducing social inequality. These life course models are not mutually exclusive but rather offer complementary frameworks for understanding the complex biosocial pathways that shape well-being across the lifespan.

Social Genomics: Unraveling the Molecular Mechanisms of Biological Programming

While genetic inheritance plays a role in our health and behavior, the emerging field of social genomics emphasizes the dynamic interplay between our genes and our environment, particularly our social environment. Social genomics explores how external social conditions can influence the activity of our genome, providing a molecular understanding of biological programming.

While our DNA sequence is fixed, the expression of our genes – which genes are “turned on” or “off” – is highly responsive to environmental cues. Social genomics focuses on gene expression (transcriptome) and epigenetics (epigenome) to understand how social experiences can alter gene activity and subsequently impact our physiology, behavior, and health.

Research in social genomics is revealing that social experiences, such as social status, social support, early life adversity, and exposure to stressors, can indeed alter the expression of hundreds of genes in a coordinated manner. These changes in gene expression, driven by social experiences and reflecting biological programming, can have long-term consequences for health and development.

Epigenetics, meaning “above” or “on top of” genetics, focuses on chemical modifications to our DNA and its packaging that alter gene accessibility and expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. DNA methylation, a key epigenetic mechanism, involves adding methyl groups to DNA, influencing gene activity. Epigenetic modifications are relatively stable and can be passed down during cell division, providing a biological “memory” of past environmental exposures.

Epigenetics offers a molecular mechanism for biological programming, explaining how our bodies “remember” early life experiences and how these experiences can have lasting effects on gene expression and health. Analyzing DNA methylation patterns at different life stages can reveal how environmental, behavioral, and biological trajectories have shaped our gene expression profiles.

Furthermore, epigenetic changes can be transmitted across generations, even without direct environmental exposure in subsequent generations. Studies in animals and humans suggest that parental experiences, such as stress or nutritional deprivation, can induce epigenetic changes that are inherited by offspring, influencing their health and development. This intergenerational epigenetic inheritance adds another layer of complexity to biological programming, suggesting that the impact of social environments can extend beyond a single generation.

Social genomics is a rapidly evolving field offering unprecedented opportunities to understand the molecular mechanisms of biological programming. By unraveling how social environments regulate gene expression, we can gain deeper insights into the biological pathways linking social experiences to health and social inequalities. This knowledge can pave the way for targeted interventions aimed at modifying environmental exposures to promote health equity and break cycles of disadvantage across generations.

Conclusion: Embracing Biological Programming in Health and Social Care

Understanding biological programming in health and social care is no longer a niche academic pursuit but a crucial imperative for improving population health and reducing social inequalities. By recognizing that early life experiences, shaped by social contexts, can profoundly and lastingly alter our biology, we can move beyond simplistic nature versus nurture debates and embrace a more nuanced and comprehensive biosocial approach.

The research highlighted here demonstrates the power of integrating biological insights into social science frameworks. From neighborhood effects on cellular aging to the impact of discrimination on sleep, and the effects of economic recession on immune function, biosocial research is revealing the intricate pathways through which social environments “get under the skin.”

Furthermore, life course perspectives and social genomics are providing deeper understanding of the temporal and molecular dimensions of biological programming. By tracing the unfolding of biological programming across different life stages and unraveling the epigenetic mechanisms involved, we are gaining unprecedented insights into how early experiences shape lifelong health trajectories.

Moving forward, embracing biological programming in health and social care requires several key steps:

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Fostering collaborations between social scientists, biologists, medical professionals, and policymakers is essential to translate biosocial research into practical applications.

- Life Course Interventions: Developing interventions that target critical periods of development and address social determinants of health early in life can mitigate the negative impacts of biological programming and promote healthy trajectories.

- Policy Implications: Integrating the understanding of biological programming into social policies, such as early childhood education, poverty reduction programs, and healthcare access initiatives, can create more equitable and health-promoting environments for all.

- Further Research: Continued investment in biosocial research, particularly longitudinal studies and social genomics research, is crucial to further unravel the complexities of biological programming and identify novel intervention points.

By embracing the concept of biological programming, health and social care can move towards a more preventative, personalized, and equitable approach. Recognizing the profound and lasting impact of early life experiences on our biology empowers us to create healthier societies for present and future generations.

Biography

Thomas McDade is the Carlos Montezuma Professor of Anthropology and Faculty Fellow of the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University. He is also a Senior Fellow in the Child and Brain Development Program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

Kathleen Mullan Harris is the James E. Haar Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Faculty Fellow of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is also a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and Director of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health).

Footnotes

1In 2008, Social Biology was renamed to Biodemography and Social Biology, the journal of the Society for Biodemography and Social Biology.

Contributor Information

Kathleen Mullan Harris, University of North Carolina, 206 W. Franklin St., Chapel Hill, NC 27516-3997, Phone: 919-962-6158, [email protected].

Thomas W. McDade, Northwestern University, 1810 Hinman Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208, Phone: 847/467-4304, [email protected]

References cited