Introduction

Over the past two decades, pay-for-performance (P4P) models have emerged as a strategy to enhance healthcare delivery, aiming to ensure clinical quality and improve patient health outcomes. These incentive-based systems are designed to reward healthcare providers for meeting specific performance targets, ideally driving improvements in care. However, the actual impact of P4P on health outcomes is still debated, with research indicating mixed results. A key factor often cited as limiting the effectiveness of P4P programs is the variable engagement of healthcare professionals.

This article delves into the perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding P4P programs, drawing upon a qualitative metasynthesis of existing research. By synthesizing findings from multiple qualitative studies, we aim to understand how healthcare professionals view P4P in their daily clinical practice. This analysis reveals crucial themes related to their experiences, which are essential for shaping future research and the development of more effective value-based payment models.

The central question this article addresses is: Do You Believe P4p Programs Work To Improve Patient Care from the perspective of healthcare professionals? Understanding their viewpoints is critical because their engagement is paramount to the success of these programs. Insights gained from this synthesis can inform the design and implementation of payment models that are more likely to achieve their intended goals of enhancing clinical quality and ultimately, patient outcomes.

Understanding Pay-for-Performance (P4P) Programs

Pay-for-performance (P4P) is a type of value-based payment (VBP) model that has become increasingly common in healthcare. The push for these models began in 2001 when the Institute of Medicine (IOM) highlighted the need for significant healthcare system reform to simultaneously improve patient outcomes and control rising costs. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines P4P broadly as any payment arrangement that links provider payments to performance, including cost-related measures.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been a major driver of P4P adoption in the U.S., implementing changes to Medicare reimbursements to incentivize hospitals and outpatient providers. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015 further solidified P4P through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Globally, programs like the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) in the United Kingdom, launched in 2004, illustrate the widespread interest in P4P as a mechanism to drive quality improvement in diverse healthcare systems.

Despite the growing prevalence of P4P, evidence of its consistent positive impact on health outcomes or cost reduction remains inconclusive. The effectiveness of P4P programs is influenced by numerous factors, including program design and the specific healthcare environment. Crucially, the level of engagement from physicians and other healthcare professionals in both the design and execution of P4P initiatives is considered a vital determinant of success. Economic theories suggest that financial incentives should modify provider behavior, but the reality is far more complex. Behavioral responses to incentives can be unpredictable and are shaped by a multitude of factors.

Research has shown that while P4P programs might initially lead to improvements in quality outcomes, the long-term effects and the underlying motivations of healthcare providers are critical considerations. Studies have indicated that many providers view the concept of P4P favorably in principle but are less convinced of its practical application and the accuracy of the data used to measure performance. Mistrust in payers and a lack of provider support can even undermine the intended positive effects of P4P. Therefore, understanding the perceptions of healthcare professionals is essential to optimize these payment models and enhance their effectiveness.

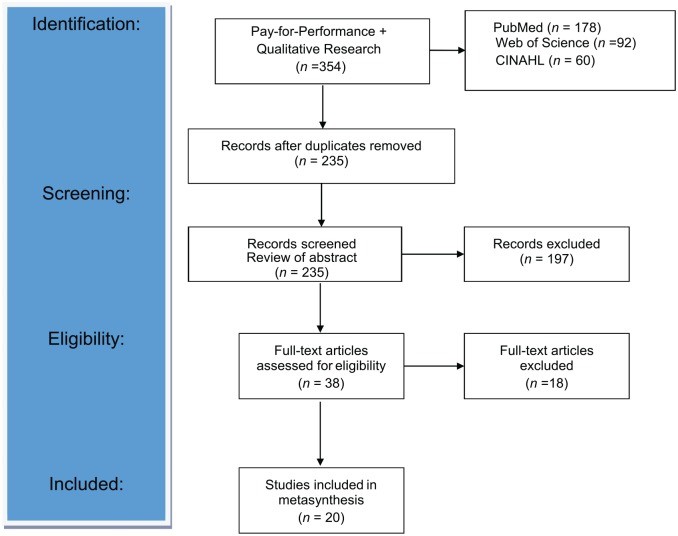

PRISMA flowchart study selection process for qualitative metasynthesis on pay-for-performance perceptions.

Methods: Synthesizing Qualitative Research

To explore the question of whether P4P programs are perceived to effectively improve patient care, this study employed a qualitative metasynthesis approach. This method systematically synthesizes findings from multiple qualitative studies to provide a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon—in this case, healthcare professionals’ perceptions of P4P programs. The metasynthesis involved a rigorous process encompassing several key stages: a systematic literature search, quality appraisal of selected studies, thematic synthesis, and reciprocal translation.

The systematic search for relevant literature was conducted across PubMed, Web of Science, and CINAHL databases, focusing on studies published between January 2000 and February 2019. The search terms included “P4P AND qualitative research” or “qualitative study,” targeting research that explored the experiences and perspectives of healthcare professionals regarding pay-for-performance initiatives. Studies were included if they were published in English, involved human subjects, and presented primary qualitative data related to healthcare professionals’ views on P4P in clinical practice.

Studies were excluded if they lacked primary qualitative data, focused on patient or caregiver perspectives, pertained to hospital-wide or nursing home P4P programs (to concentrate on outpatient primary care), or were dissertations, reviews, grey literature, or mixed-methods research. The focus on primary care settings was intentional, as these are the most common sites for P4P program implementation globally. Mixed-methods studies were excluded to ensure a focus on research primarily driven by qualitative inquiry, which is best suited to explore perceptions and experiences in depth.

The study selection process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure transparency and methodological rigor. Initially, 235 articles were identified. After a thorough review of titles and abstracts, and subsequent full-text reviews, 20 articles were selected for the final metasynthesis. This selection represents a saturation of themes, indicating a comprehensive representation of the existing qualitative research on healthcare professionals’ perceptions of P4P.

Data extraction and quality assessment were performed on each of the 20 included articles. The McMaster University Tool, a 17-domain instrument designed for qualitative research appraisal, was used to evaluate the rigor of each study. This assessment ensured that only high-quality studies contributed to the synthesis. The included studies spanned various countries—both developed and low-income—to capture a broad range of perspectives across different healthcare contexts and institutional settings. This diversity allowed for the identification of common themes related to healthcare professional engagement with P4P, despite variations in program design and setting.

The data synthesis and analysis phase involved a thematic approach. The research team independently reviewed each study, identifying key themes and subthemes related to healthcare professionals’ perceptions of P4P. Thematic content from each study, including participant quotes and author interpretations, was coded and analyzed to identify recurring patterns and concepts. Discussions and comparisons among the research team members facilitated an iterative process of theme development and refinement. A reciprocal translation table was used to map themes across studies, ensuring coherence and corroboration of findings. This rigorous analytical process enabled the synthesis of interpretations across studies, leading to the identification of four overarching themes that answer the central research question about healthcare professionals’ perceptions of P4P programs and their impact on patient care.

Key Themes: Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of P4P

The qualitative metasynthesis revealed four key themes that encapsulate healthcare professionals’ perceptions of pay-for-performance (P4P) programs:

- Positive Perceptions of Performance Measurement and Financial Incentives: This theme highlights the recognized value of quality targets in improving patient care processes and aligning with professional values.

- Negative Perceptions of Performance Measurement and Financial Incentives: This theme encompasses concerns about the validity of performance measures, unintended consequences like “box-checking,” and doubts about the impact of financial incentives on care delivery.

- Perceptions of P4P’s Influence on Quality and Appropriateness of Care: This theme explores how P4P programs are seen to affect health equity, patient-centered care, and the patient-provider relationship.

- Perceptions of P4P’s Influence on Professional Roles and Workplace Dynamics: This theme examines the impact of P4P on team dynamics, professional roles, workflow changes, and the importance of physician involvement in program development.

These themes provide a structured understanding of the complex and often contradictory views healthcare professionals hold regarding P4P programs and their effectiveness in improving patient care.

Theme 1: Positive Perceptions of Performance Measurement and the Associated Financial Incentive

A significant finding across the studies was that healthcare professionals often acknowledge the potential value of performance measurement and associated financial incentives in P4P programs. They recognize that these programs can drive improvements in patient care processes and align with their professional goals of providing high-quality care. The underlying assumption is that the performance measures are meaningful, relevant, and can be influenced by the actions of healthcare professionals and organizations.

Quality Targets Improve Patient Care Processes

Many participants in the studies believed that the quality targets embedded in P4P programs lead to tangible improvements in patient care. Physicians noted that these targets focus attention on essential clinical activities, ensuring that important aspects of care are not overlooked. One clinician remarked that quality measures are “important because they do help to improve…health.” Another participant emphasized the value of feedback on performance against quality targets, noting that it provides valuable insight into their clinical practice. A general practitioner (GP) commented, “I thought I was doing well, but now I get more insight into what happens.”

Providers also expressed that quality targets offer motivation and direction for improving care. A GP stated, “Most GPs are now motivated to perform well on certain quality issues… I mean it wasn’t there before—there wasn’t any quality, it was all about quantity.” This sentiment suggests a recognition that P4P programs can shift the focus from volume-based to value-based care, prioritizing quality over quantity.

Several respondents reflected on a perceived lack of standardization in care prior to P4P implementation. One GP described past practices as “terrible” and noted that P4P ensures “that those GPs work to a certain standard.” A clinic nurse highlighted the patient benefits of P4P, stating, “It’s benefiting the patients, that they don’t get missed, they don’t slip through the net, they get their medicines reviewed, they get their blood tests done, they’re kept on the optimum treatment.” This underscores the perception that P4P programs can create more systematic and reliable care processes, ultimately benefiting patients.

Furthermore, many healthcare professionals acknowledged that performance measures and quality targets are typically based on evidence-based medicine. This alignment with established clinical guidelines was seen as a positive aspect, enabling practices to standardize care around best practices. While there was general agreement on the value of evidence-based targets, some skepticism emerged regarding the rigidity of these measures in the complex reality of primary care. One GP suggested making the targets “less black and white,” recognizing that “sometimes medicine isn’t like that” and that clinical judgment often requires navigating “grey areas.”

Alignment With Professional Values and Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation, driven by a sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose, is a significant factor influencing healthcare professionals, especially physicians. Participants in the studies suggested that P4P programs often legitimize their intrinsic motivation to improve patient outcomes. As one nurse/midwife put it, “Personally, the incentives are just an addition, but my spirit is to help people. Nursing is a calling.” This indicates that for many, the financial incentive is secondary to their inherent drive to provide good care.

P4P programs were also seen as a “wake-up call,” highlighting discrepancies between current practice and ideal care standards. A GP noted, “It’s just an additional motivation to make sure that we are practicing good practice.” This suggests that P4P can serve as a catalyst for self-reflection and practice improvement, reinforcing existing professional values.

However, concerns were raised about the potential conflict between P4P targets and physician autonomy in clinical decision-making. Some physicians expressed a need to maintain control over clinical targets to accommodate individual patient needs and the inherent variability of patient care. One GP warned that “the more templates that get introduced, it takes away the clinician’s freedom.”

Interestingly, competition, both within and between clinics, emerged as a positive driver of behavior change, often without negatively impacting intrinsic motivation. A GP observed, “GPs, and doctors by nature are competitive, and so one wants to get all the brownie points.” A practice manager echoed this, noting, “It does feel a bit like a competition with other surgeries. I wouldn’t like to come in last.” This competitive element, alongside financial incentives, can enhance motivation and engagement in P4P programs.

Financial incentives themselves were generally viewed positively, especially when framed as rewards for quality rather than utilization control. Incentivizing for quality was seen as more palatable and aligned with professional values. A practice executive stated, “The idea of a quality incentive is probably easier to swallow than the previous financial incentives that were offered to us.” Improved morale among physicians and other healthcare professionals was also reported as a benefit of financial incentives, reinforcing their value in the context of P4P programs.

While the literature often points to potential tensions between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivators like financial incentives, the healthcare professionals in these studies often viewed them as complementary, rather than conflicting, forces in driving quality improvement.

Theme 2: Negative Perceptions of the Performance Measurement and the Associated Financial Incentive

Despite the positive aspects, healthcare professionals expressed significant negative perceptions regarding performance measurement and financial incentives within P4P programs. These negative views often centered on concerns about the validity of the measures themselves, the unintended consequences of focusing on incentivized metrics, and doubts about whether financial incentives genuinely alter care delivery.

The Performance Measures as a Measurement of Quality

A primary concern was whether performance measures accurately reflect the quality of care provided. Respondents questioned if what was being measured truly represented quality, suggesting that the metrics might be inconsistent with their professional definitions of quality care. One participant argued, “Quality is so much more than this [quality target] could ever get at, for me. Because quality is continuity of care. It’s that I know my patients. That they know me. That they trust me.” This quote highlights a perception that quantifiable measures may overlook crucial, less tangible aspects of quality, such as the patient-provider relationship and continuity of care.

Credibility of performance measurement was another recurring concern. Healthcare professionals doubted the accuracy of data, both in terms of recording and reporting processes, and expressed skepticism about data derived from third-party sources like health plans. A practice executive questioned, “The difficulty is in the measurement. It’s how you measure. What are the measures? Are the measures valid for consumers? Are the statistics, are they done correctly? Are they shown correctly?” This skepticism about data integrity undermined confidence in the fairness and validity of P4P assessments.

Furthermore, the utility of performance feedback was inconsistent. While some acknowledged the potential of timely and accurate data with feedback to improve practice, others reported not using the feedback provided or questioning its relevance to their daily practice. This variability in the perceived value of feedback suggests that the design and delivery of performance data are critical factors in its effectiveness.

Unintended Consequences: Box-Checking, Measure Fixation, and the Potential for Gaming

A consistent negative theme was the perception that P4P programs can lead to “box-checking” and an excessive focus on meeting measured targets, potentially at the expense of holistic patient care. This “measure fixation” was seen as creating tension within clinical practice. One GP worried, “if this is going to become a tick-the-box exercise it might be that the question will be pushed at an inappropriate time, the wrong moment for the sake of some points.” Another respondent simply stated, “the boxes were checked,” implying a perfunctory approach to meeting targets without genuine integration into care practices.

Nurses were often delegated the responsibility of “checking the boxes,” which, while potentially streamlining processes, could also depersonalize patient interactions and reduce the focus on individual patient needs. This concern was exacerbated by the increasing reliance on health information technology (HIT) for performance measurement. A practice nurse lamented, “I feel actually I am looking at the patient less than I used to, which is a shame… I’ve got to look at the computer as well and type in while you’re talking to me.” Another GP echoed this, noting that they might be spending more time attending to computer prompts than engaging with patients.

The potential for P4P programs to incentivize specific clinical areas over others raised concerns about unintended consequences for overall patient care. Healthcare professionals worried that providers might prioritize incentivized activities at the expense of addressing other important patient needs. One GP warned that providers might be “pushed by these performance measures and just add on drugs to treat the performance measure,” potentially leading to inappropriate polypharmacy. Another physician noted that providers might focus on “alerts” related to performance measures rather than addressing the patient’s presenting complaint. A GP gave a stark example: “I went through the cholesterol, the depression, the CHD, and everything else and ‘Oh that’s wonderful I’m finished now,’ and the patient said, ‘well what about my foot then?'” These anecdotes illustrate the potential for P4P to narrow clinical focus and devalue non-incentivized aspects of patient care.

Furthermore, the potential for “gaming” the system was identified as an unintended consequence. While most respondents didn’t admit to gaming themselves, they suspected that others might manipulate data submissions or exclude certain patients to improve performance scores. This potential for manipulation undermines the integrity of P4P programs and raises ethical concerns about their true impact on patient care.

Financial Incentives Have No Impact on Care Delivery

A segment of healthcare professionals believed that financial incentives simply did not alter care delivery. This perception stemmed from several factors, including the perceived inadequacy of the incentive amount, a lack of awareness about the incentives, or a fundamental belief that financial rewards do not change clinical behavior.

The monetary value of the incentives was often seen as insufficient to motivate significant changes in practice. A practice nurse questioned the ethical basis of incentives, stating, “We’re paid to do it anyway. Why is it that there’s extra money given when you’re given a wage to do it anyway? I don’t know why a carrot should be dangled. Personally, I find it immoral.” In a low-income setting, a clinical officer in Malawi described the incentive as “almost nothing,” questioning its motivational value in the context of economic realities.

Some respondents expressed resentment at the idea that financial incentives were necessary to drive quality, viewing it as an insult to their professional commitment. They felt that the incentives implied that quality care was not already being provided. Many viewed the incentive payments as “money already owed,” a bonus for care they were already delivering to the best of their abilities. As one practice executive stated, “Good physicians are just good physicians… they do what’s best for the patient,” suggesting that intrinsic motivation is the primary driver of quality care, not financial rewards.

Theme 3: Perception of How P4P Programs Influence the Quality and Appropriateness of Care

Healthcare professionals also voiced concerns about how P4P programs might negatively influence the quality and appropriateness of care, particularly in relation to health equity and patient-centeredness. These concerns highlight potential drawbacks of P4P that could undermine its intended benefits.

The Unintended Negative Consequences of P4P on Health Equity

One significant concern was the potential for P4P programs to exacerbate existing health inequities. Respondents questioned the fairness and relevance of standardized quality targets across diverse patient populations and practice settings. They pointed out that clinics serving socioeconomically disadvantaged populations might struggle to meet the same targets as better-resourced practices, leading to unintended penalties and widening disparities.

It was suggested that clinics with greater resources could more easily invest in the necessary infrastructure and care redesign to succeed in P4P programs. Furthermore, preventive measures that require patient engagement might be harder to achieve in populations facing social and medical complexities. A provider working in a safety net clinic explained, “In the populations we serve… it’s harder to get patients engaged in their disease processes… when [they’re] trying to survive… all other things just fall to the side.” This highlights the challenges of applying uniform performance metrics to populations with vastly different social determinants of health.

The concern was that P4P, if not carefully designed, could inadvertently penalize practices that serve vulnerable populations, further disadvantaging those most in need of high-quality care. A practice executive warned that “if we don’t reward performance [and] improvement, we may exacerbate the disparities you are seeing in poorer neighborhoods.” Another provider in a safety net clinic expressed frustration, arguing that P4P is “not fair… You’re penalizing the clinics that are trying to work with people and do the best they can, from where they [patients] are coming from.” These perspectives underscore the need to consider equity implications when designing and implementing P4P programs.

Disrupted Patient-Centered Care and Devaluing the Patient’s Agenda

Another prominent concern was that P4P programs could disrupt patient-centered care, lead to a loss of holism and continuity, and erode the doctor-patient relationship. The emphasis on standardized measures and targets was seen as potentially conflicting with individualized, patient-centered approaches to care.

Respondents noted increased tensions during patient consultations and a decreased focus on patients’ unique concerns. The drive to meet performance targets might incentivize providers to prioritize measured outcomes over addressing the full spectrum of patient needs and preferences. The increasing emphasis on same-day appointments and extended hours, often incentivized by P4P, was also seen as potentially disrupting continuity of care, as patients might see different providers for each visit.

One GP observed, “In the sense that it’s still a patient presenting to the doctor with a problem, yes, it is the same as it always was. The difference is that it is more likely that the patient and the doctor won’t know each other.” Another GP lamented, “We have become so measurement-oriented, it’s becoming more difficult for the patient and the doctor to have a genuine personal relationship around the patient’s own circumstances.” These comments suggest that P4P programs, while aiming to improve specific aspects of care, might inadvertently undermine the relational and holistic dimensions of patient-centered practice.

Concerns about patient autonomy were also raised. Healthcare professionals worried that the focus on performance measures could lead to devaluing patients’ agendas and preferences. There was concern that providers might become overly directive in pushing for recommended interventions to meet targets, potentially overriding patient autonomy. One RN noted that the system “does not let you refuse… it’s like you’re trying to break [the patients] down and eventually make them give in,” highlighting the potential for P4P to create pressure on patients to comply with recommended care, even against their wishes.

Theme 4: Perceptions of the Influence of the P4P Program on Professional Roles and Workplace Dynamics

Beyond the direct impact on patient care, healthcare professionals also described significant influences of P4P programs on their professional roles and workplace dynamics. These changes, while sometimes viewed positively, often introduced new tensions and complexities into the healthcare environment.

Performance Measurement and Associated Financial Incentives Creates Tension Amongst Team Members

The implementation of P4P programs often necessitates changes in practice structure, including enhanced performance monitoring, workflow redesign, and quality improvement initiatives. This can lead to new team dynamics and, at times, increased workplace tension. The introduction of designated individuals to monitor team performance was sometimes perceived as “surveillance” or “policing,” particularly when nurses or other staff were tasked with monitoring physician performance.

A clinical lead described using “naming and shaming” as a strategy to improve performance, highlighting the potential for P4P to create a competitive and potentially stressful work environment. One GP noted an “environment and ethos of increased surveillance and performance monitoring,” while a practice nurse echoed this, stating, “it feels more like I am being watched. It’s a little bit like big brother.” These comments illustrate how P4P can alter the perceived autonomy and trust within healthcare teams.

Financial incentives themselves could also be a source of tension, particularly regarding their distribution and perceived fairness. In programs where incentives were not equally distributed across team members, or where the criteria for distribution were unclear, resentment and distrust could arise. One staff member in a P4P program in Tanzania argued that “the money should be shared equally to all because all workers have their own responsibilities.” An RN in another study expressed frustration that providers seemed to be the primary beneficiaries of incentives, while non-physician staff felt their contributions were undervalued. These concerns about fairness and transparency in incentive distribution underscore the importance of considering team dynamics when designing P4P programs.

Tension Over Changing Professional Roles

P4P programs often led to changes in professional roles and responsibilities, particularly for physicians and nurses. Physicians sometimes expressed tension over these altered roles, perceiving a potential “deskilling” as tasks traditionally performed by doctors were delegated to other team members, such as nurses taking on chronic disease management. One GP described feeling, “a little bit of deskilling there” as nurses took over routine asthma checks, leading to a sense of diminished confidence in managing these conditions independently.

Conversely, nurses often experienced expanded roles and increased autonomy under P4P, which was generally viewed positively, despite often leading to increased workload and stress. One practice nurse noted that the increased autonomy made the job “more fulfilling,” providing a sense of “responsibility or ownership.” However, even with expanded roles for nurses, some physicians maintained a sense of ultimate ownership and accountability for patient care, highlighting the complex negotiation of roles within P4P-driven team structures. As one GP stated, “Nurses are very good at doing things… but the overall medical control will always come back to us.”

The emergence of “practice champions” for P4P implementation was also noted as a significant factor in program success. These individuals, who could be from various care team roles, took ownership of P4P initiatives, facilitating team engagement and streamlining workflow changes. A practice manager emphasized the importance of having “someone that’s responsible for it, their baby, they’ve got an interest in it, and they will drive it through,” highlighting the value of dedicated leadership in navigating the complexities of P4P implementation.

Changes to Workflow and Care Delivery: Evolution and Adaptation

Experience with P4P programs led to significant changes in clinic workflow and care delivery. Participants described a standardization of care and practice operations, driven by the need to meet performance targets. “Most physician organizations worked to reduce practice variation,” noted one study. Practices often had to invest time and resources in infrastructure changes and care redesign to adapt to P4P requirements. Difficulties with data extraction from electronic medical records were also cited as a burden. Overall, participants emphasized the need for efficient processes and adequate infrastructure to be in place before P4P programs are launched.

Despite initial challenges, healthcare professionals demonstrated remarkable adaptability over time. Concerns about changes to clinical practice, altered roles, and a perceived move away from holistic care were often counterbalanced by a recognition of the benefits of more structured, planned care, more informed patients, and improved reporting and feedback systems. As one nurse reflected, “[Previously] it was very much more individualistic… some might be ignored completely.” This suggests that while P4P introduces challenges, it also fosters evolution and adaptation in care delivery, leading to potential improvements in system-level organization and patient tracking.

Physician Input: Value of Including Physicians in Program Development

A consistently emphasized theme was the importance of including physicians and other healthcare professionals in the development and implementation of P4P programs. Respondents believed that provider buy-in is much easier to achieve when program designers ensure the relevance of measures and the feasibility of implementation from a practice perspective.

One general internist argued for provider involvement in defining quality measures, stating, “I think there is an opportunity to actually help define what quality is… and actually taking a stand on what it is that we feel we should be evaluated on, not [leaving P4P development to] some outside organization.” Many believed that physician engagement in program design would directly influence program success. A GP noted, “I think that’s tremendously important that GPs feel they have some form of participation in generating indicators. I think it completely changes your relationship from feeling it’s some sort of diktat handed down from on high to thinking we’re all involved.” These perspectives underscore the critical role of collaborative program design in fostering provider engagement and maximizing the effectiveness of P4P initiatives.

Discussion: Balancing Incentives and Patient Care

This metasynthesis provides valuable insights into healthcare professionals’ perceptions of P4P programs and their impact on patient care. The findings reveal a complex landscape of both positive and negative views, highlighting the multifaceted nature of P4P implementation in clinical practice. While P4P programs are intended to improve patient care by incentivizing quality, the perspectives of those delivering the care reveal crucial considerations for optimizing these models.

Healthcare professionals recognize the potential of P4P to standardize care based on evidence and to create systems for consistent patient tracking. They appreciate the focus on quality improvement and the alignment with evidence-based practices. However, significant concerns emerge regarding the validity of performance measures, the potential for unintended consequences like measure fixation and compromised patient-centeredness, and the risk of exacerbating health inequities.

The study underscores that do you believe P4P programs work to improve patient care is not a simple yes or no question for healthcare professionals. Their beliefs are nuanced and depend on various factors, including program design, implementation, and the specific context of their practice. The metasynthesis highlights that while incentives can motivate certain behaviors, they also introduce complexities and potential downsides that must be carefully managed.

One critical takeaway is the need to ensure that performance measures genuinely reflect quality and value, as defined not just by payers but also by providers and patients. Measures should be relevant, valid, and sensitive to the diverse needs of patient populations. Furthermore, programs must be designed to mitigate unintended consequences, such as “box-checking,” narrowed clinical focus, and compromised patient autonomy. Addressing the potential for P4P to worsen health disparities is also paramount, requiring careful risk adjustment and consideration of social determinants of health.

The financial incentives themselves are a complex issue. While some healthcare professionals view them as motivators and recognition of their efforts, others are skeptical of their impact or even resentful of their implication. As payment models evolve beyond P4P towards more comprehensive risk-sharing arrangements, understanding provider perceptions of financial incentives and their perceived impact on care quality remains crucial. Engaging healthcare professionals in the design and communication of these models is essential to foster buy-in and ensure alignment with professional values.

The metasynthesis also illuminates the significant impact of P4P on professional roles and workplace dynamics. While P4P can drive team-based care and empower non-physician staff, it can also create tensions and alter traditional professional identities. Recognizing and addressing these changes, and fostering collaborative team environments, are critical for successful P4P implementation. The importance of physician engagement in program development cannot be overstated. Involving healthcare professionals in the design and selection of measures, and in the ongoing evaluation and refinement of P4P programs, is essential to ensure their relevance, feasibility, and ultimate effectiveness in improving patient care.

Limitations

This metasynthesis, while providing valuable insights, has limitations. The analysis relies on published qualitative studies, which may not always fully capture the diverse perspectives within healthcare teams. The specific roles and viewpoints of advanced practice providers and other non-physician staff could be further explored in future research. Additionally, the included studies span a considerable time period, reflecting potentially evolving perceptions of P4P over time and across different stages of program implementation. Future research could focus on the longitudinal evolution of healthcare professionals’ views and the impact of accumulated experience with P4P programs.

Conclusion: Towards More Effective Value-Based Payment Models

The findings of this metasynthesis underscore that healthcare professionals are adaptable and not inherently opposed to incentive-based payment models. However, their perceptions of P4P programs are shaped by a complex interplay of factors, highlighting both the potential benefits and inherent challenges of these approaches. The four key themes identified—positive perceptions of measurement, negative perceptions and unintended consequences, impact on quality and equity, and influence on professional roles—provide a framework for understanding these perceptions.

Ultimately, to effectively answer the question do you believe P4P programs work to improve patient care, a balanced and nuanced approach is needed. P4P programs can be a valuable tool for driving quality improvement, but their success hinges on careful design, thoughtful implementation, and, crucially, the active engagement of healthcare professionals. Future research should continue to explore care team perceptions of P4P, using the themes identified in this metasynthesis to develop a conceptual framework for guiding inquiry and program development. By incorporating the perspectives of those on the front lines of care delivery, and by adopting a continuous quality improvement approach, we can move towards value-based payment models that are more effective, equitable, and truly patient-centered.

References

(References are in the original article and should be included here for completeness in a real-world scenario)

Supplemental Material

(Supplemental material link from original article to be included here)