Introduction

In response to the 1987 Omnibus Reconciliation Act, nursing homes have implemented restorative care programs aimed at maximizing each resident’s functional capabilities. Since 1998, Medicare has offered additional reimbursement to Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) providing these programs, specifically for engaging residents in at least two restorative care activities for a minimum of 15 minutes daily, six days a week. These activities encompass a range of crucial functions, including walking, range of motion exercises, bed mobility, transferring, dressing, grooming, eating, swallowing, communication, and the management of splints, braces, and prostheses. This reimbursement policy was initiated based on the findings of the Nursing Home Case Mix and Quality Demonstration project (Reilly, Mueller, & Zimmerman, 2007). However, a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of these Medicare-supported Restorative Care Programs Nursing Homes offer has been lacking, creating a gap in knowledge critical for guiding future practices and research.

Restorative care, in a broader sense, is a philosophy centered on evaluating a resident’s functional potential and actively working to optimize and maintain these abilities (Resnick, Galik, & Boltz, 2013). The literature identifies two primary approaches to restorative care: dedicated and integrated. Medicare-supported programs often adopt a dedicated approach, where specialized staff deliver activities in scheduled 15-minute sessions to residents showing functional decline or needing to sustain gains from therapy (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, n.d.). Nursing staff typically decide program participation based on observed decline and perceived potential benefit, yet detailed understanding of participant selection remains limited (Vahakangas, Noro, & Bjorkgren, 2006). Conversely, the integrated approach emphasizes training all staff to incorporate function-promoting activities into daily care interactions with all residents. Despite these different strategies, robust empirical evidence supporting either approach is scarce. A notable randomized clinical trial involving 487 residents across 12 nursing homes, focusing on an integrated approach, showed improvements in specific mobility aspects like gait, balance, and stair climbing, but did not find significant improvements in overall Activities of Daily Living (ADL) function (Resnick et al., 2009). Quasi-experimental studies have presented mixed results, indicating improvements (Chang, Wung, & Crogan, 2008; Morris et al., 1999), maintenance (Galik et al., 2008), and even deterioration in ADL dependency (Resnick et al., 2006). This study aims to evaluate the impact of Medicare-supported restorative care programs nursing homes implement to contribute to the evidence base for effective program design and implementation.

Long-stay nursing home residents, those residing in facilities for over six months (comprising over 70% of the population on any given day, Center for Disease Control and National Center for Health Statistics, n.d.), are particularly relevant for restorative care. This group often experiences increasing ADL dependency linked to resident and facility characteristics (Arling, Kane, Mueller, Bershadsky, & Degenholtz, 2007; McConnell et al., 2003; Wang, Kane, Eberly, Virnig, & Chang, 2009). Resident factors associated with ADL dependency include advanced age, female gender, and extended length of stay (Ang, Au, Yap, & Ee, 2006; Peres, Verret, Alioum, & Barberger-Gateau, 2005). Medical conditions such as arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, COPD, depression, multiple chronic illnesses, and stroke also contribute (Ang et al., 2006; Arling et al., 2007; Fried & Guralnik, 1997; Frytak, Kane, Finch, Kane, & Maude-Griffin, 2001). Physical impairments in balance, gait, and range of motion further exacerbate dependency (Ang et al., 2006; Arling et al., 2007; Fried & Guralnik, 1997; McConnell et al., 2003; Sakari-Rantala, Era, Rantanen, & Heikkinen, 1998; Wang et al., 2009). Nursing home characteristics, including size, staffing levels, leadership certification, and ownership type, can also influence ADL dependency (Arling et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009). Demonstrating the effectiveness of restorative care programs nursing homes offer for long-stay residents is crucial for optimizing participant selection and program impact.

The Minimum Data Set (MDS), mandated for all Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing homes, provides standardized resident health assessments and reports restorative care provision. Recent availability of MDS data linked to the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey offers a valuable resource to describe participant characteristics and assess the effectiveness of Medicare-supported restorative care programs nursing homes utilize. This study leverages this nationally representative MDS data to: (a) determine the prevalence of long-stay residents receiving restorative care and the prevalence of nursing homes offering such programs, (b) compare characteristics of residents receiving and not receiving restorative care, and (c) evaluate the impact of restorative care on changes in ADL dependency. The primary hypothesis is that participants in restorative care would exhibit a slower decline in ADL dependency over 18 months compared to nonparticipants, even after considering resident (age, length of stay, cognitive impairment, frailty, comorbidities, mood, social engagement, pain, physical impairments, baseline ADL function, and nurse assessment of improvement potential) and nursing home characteristics (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement percentage, nursing contact hours, medical director and director of nursing certification, and facility accreditation). The findings aim to inform future research and refine restorative care practices.

Design and Methods

This study employed a longitudinal analysis of nursing home MDS data linked with the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey (NNHS), a nationally representative survey. Data access was granted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) following study protocol approval, and accessed through the Minnesota Census Research Data Center due to restricted use variables. Resident data originated from the MDS, while nursing home characteristics were sourced from the NNHS.

Sample

The study focused on long-stay residents aged 65 years or older, residing in nursing homes for at least six months, deemed likely to benefit from restorative care programs nursing homes. Exclusion criteria included residents who were bedfast, in a persistent vegetative state, with a prognosis of six months or less, or with end-stage disease, as their potential for functional maintenance or improvement was considered limited. Residents receiving concurrent occupational, physical, or speech therapy were also excluded to isolate the effect of restorative care. Figure 1 details the sample selection process and attrition.

Longitudinal Dataset

An 18-month longitudinal dataset was constructed using admission, quarterly, significant change, and annual MDS assessments from 2003-2006 for eligible residents. Quarterly time points (baseline, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months) were established, using the most recent assessment within each 3-month period (only 7% from significant change assessments). The 18-month timeframe was chosen to assess long-term effects, aligning with recommendations for evaluating rehabilitation sustainability (Forster et al., 2009). Baseline MDS variables were derived from the first full or admission assessment, and NNHS nursing home characteristics were treated as static baseline variables. Table 1 outlines variable sources. Figure 1 illustrates the attrition rate, with 60% of residents remaining in the dataset at 18 months.

MDS Variables

MDS Psychometric Properties

The MDS 2.0, widely used in outcome and evaluation studies, has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity. Over 85% of MDS items show adequate inter-rater reliability (κ > .6) (Mor, 2004). ADL scales, cognitive function, and medical diagnoses are among the most reliable and valid measures. Scales for pain, mood, and social engagement exhibit less ideal psychometric properties (Casten, Lawton, Parmelee, & Kleban, 1998; Frederiksen, Tariot, & De Jonghe, 1996; Gambassi et al., 1998; Hartmaier et al., 1995; Lawton et al., 1998; Mor, Intrator, Unruh, & Cai, 2011, Morris et al., 1990; Williams, Li, Fries, & Warren, 1997). MDS data collection relies on nursing home staff interviews and record reviews, potentially introducing facility-level variability in measurement quality (Lum, Lin, & Kane, 2005; Shin & Scherer, 2009). Facilities with reporting biases tend to exhibit them across all items (Wu, Mor, & Roy, 2009), necessitating consideration of the nursing home context in MDS data analysis. Despite these limitations, the MDS provides comprehensive, systematically collected data valuable for evaluating restorative care programs nursing homes offer in real-world settings.

ADL dependency was quantified using the MDS ADL-7 scale, an additive scale based on seven MDS items assessing self-performance in bed mobility, transferring, dressing, eating, toilet use, personal hygiene, and bathing. A 5-point Likert scale (0=independent to 4=total dependence) measures dependency levels for each activity, resulting in total scores from 0-28, with higher scores indicating greater dependency. The ADL-7 demonstrates strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > .85) (Mor, Intrator, Unruh, & Cai, 2011), moderate to strong correlations with other ADL measures (r = .58–.79) (Frederiksen et al., 1996; Lawton et al., 1998; Snowden et al., 1999), predicts nursing assistant time utilization (Morris et al., 1999), and is sensitive to change in observational and interventional studies (Carpenter, Hastie, Morris, Fries, & Ankri, 2006; Grando et al., 2009; Morris et al., 1999).

Restorative care activities are documented in the MDS as the number of days in the past week a resident received at least 15 minutes of specific interventions: passive and active range of motion, splint/brace assistance/training, and skill practice in bed mobility, transferring, walking, dressing, grooming, eating, swallowing, amputation-prosthesis care, communication, or other skills. Preliminary analyses explored restorative care operationalized in three ways: (a) dichotomously (any restorative care received), (b) as a count of activities received, and (c) continuously (sum of days each activity provided). Neither the count (p = .40) nor continuous (p = .76) variable predicted ADL dependency in univariable models and were excluded from further analysis. The dichotomous variable, predicting ADL dependency (p = .02), was used as the independent variable in the multivariate model to represent restorative care receipt and was treated as a time-varying predictor due to quarterly variation in receipt. NNHS data was used to determine the prevalence of nursing homes employing specially trained personnel for restorative care programs nursing homes.

Resident Characteristics

MDS measures for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and length of stay were utilized. A comorbidity variable, counting 10 disease categories linked to ADL decline, was created from MDS items: dementia, stroke/paralysis, arthritis, cancer, COPD, heart disease, diabetes, neurological disease, depression, and eye disease.

Cognitive impairment was assessed using the MDS Cognitive Performance Scale, a 6-level scale (scores 0-6, higher scores indicating greater impairment) with high sensitivity (.94) and specificity (.94) (Hartmaier, Sloane, Guess, & Koch, 1994; Hartmaier et al., 1995; Morris et al., 1994). A physical impairment score (0-4) was derived by awarding one point for impairments in balance, mobility, range of motion, and voluntary movement (Cronbach’s alpha = .70). Frailty was measured using the Edmonton Frailty Scale, a multidimensional scale incorporating MDS items related to cognition, health status, functional independence, social support, medication use, nutrition, mood, continence, and functional performance (scores 0-17, higher scores indicating greater frailty) (Armstrong, Stolee, Hirdes, & Poss, 2010).

The MDS social engagement scale, including six items on interactions and activity engagement, was used (scores 0-6, higher scores indicating greater engagement, Cronbach’s alpha = .79) (Dubeau, Simon, & Morris, 2006; Mor et al., 1995). The Burrow’s mood scale, based on seven MDS items, measured depressive symptoms (scores 0-14, Cronbach’s alpha > .70, validated against Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Cornell scale) (Burrows, Morris, Simon, Hirdes, & Phillips, 2000). Pain was assessed using the MDS Pain Scale, categorizing pain frequency and intensity (none, mild, moderate, severe), with good agreement (93%) and concurrent validity (κ = .71) against nurse-administered visual analog scale assessments in post-acute settings (Fries, Simon, Morris, Flodstrom, & Bookstein, 2001). A dichotomous MDS item indicating staff perception of resident capability for ADL independence improvement (Vahakangas et al., 2006) was also included.

NNHS Variables

Nursing home characteristics from the NNHS included: percentage of residents with Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, nursing staff patient contact hours, medical director and director of nursing certification status, and facility accreditation. Nursing staff patient contact hours represented average full-time equivalent hours spent on patient care by registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nursing assistants. Medical director certification was a dichotomous variable indicating certification in family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics, or palliative care. Director of nursing certification indicated certification from relevant professional organizations. Facility accreditation was a dichotomous variable for accreditation by recognized bodies. State of nursing home residence was included as a random effect to account for variations in restorative care programs nursing homes reimbursement policies and regional MDS data collection practices.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the prevalence of residents receiving and nursing homes providing restorative care, and to describe resident characteristics. Univariable chi-square or t-tests compared baseline differences between restorative care participants and nonparticipants. Linear mixed models assessed the effect of restorative care on ADL dependency over 18 months, assuming an autoregressive covariance structure. Resident variables were time-varying predictors, and nursing home variables were static predictors. Linear models were deemed most suitable for describing ADL dependency changes. Variables with p < .05 in univariable analyses were considered for multivariable models.

The multivariable model specification is as follows:

| ADLkij=β0+b0k+b0i+β1Xkij1+…+βpXkijp +εkij, k=1,…,K, i=1,…,nk, j=1,…,nki |

|---|

Where k = state, i = subject ID, j = time point, p = number of covariates, nk = total subjects in kth state, and nkj = total time points for ith subject in kth state.

Ethical Considerations

The 2004 NNHS data collection was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board. The University of Minnesota deemed this analysis of de-identified survey data exempt from federal human research participant protection regulations. NCHS Ethical Review Board approval was also obtained for restricted data analysis through the NCHS Research Data Center.

Results

Prevalence of Restorative Care

Approximately 67% of nursing homes offered restorative care programs nursing homes. Resident participation in restorative care increased post-baseline and stabilized (24% at baseline, rising to approximately 36% from quarter 1 onwards). Walking, passive and active range of motion, and dressing/grooming were the most frequent restorative care activities (Table 2).

Table 1. List of Study Variables

| Restorative care | Activities of daily living (ADL) dependency | Resident characteristics | Nursing home characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDS items | MDS items | MDS items | NNHS items |

| Passive range of motion | ADL self-performance scale | Age | % Residents with Medicare reimbursement |

| Active range of motion | Length of stay | % Residents with Medicaid reimbursement | |

| Splint/brace assistance | Cognitive Performance Scale | Hours of patient contact with nursing staff | |

| Bed mobility | Frailty | Medical Director certification | |

| Transferring | Number of disabling diseases | Director of Nursing certification | |

| Walking | Mood | Facility accreditation | |

| Dressing/grooming | Social engagement | ||

| Eating/swallowing | Pain | ||

| Amputation/prosthesis care | Number of physical impairments | ||

| Communication | Staff assessment of resident’s ability to improve ADL dependency | ||

| Other |

Notes: MDS = minimum data set; NNHS = National Nursing Home Survey.

Table 2. Percent of Residents Participating in Restorative Care Activities by Quarter

| Restorative care activity | Baseline, N = 7,735 | Quarter 1, N = 6,719 | Quarter 2, N = 6,462 | Quarter 3, N = 6,052 | Quarter 4, N = 5,664 | Quarter 5, N = 5,279 | Quarter 6, N = 4,676 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive range of motion | 8.9 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 13.4 | 12.9 |

| Active range of motion | 10.7 | 16.8 | 17.7 | 17.2 | 17.3 | 17.4 | 16.8 |

| Splint/brace assistance | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| Bed mobility | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Transferring | 4.4 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 5.9 |

| Walking | 9.3 | 15.7 | 16.1 | 16.0 | 15.1 | 14.4 | 14.7 |

| Dressing/grooming | 4.7 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 7.0 |

| Eating/swallowing | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| Amputation/prosthesis | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Communication | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Other | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| Received any activity | 24.1 | 35.0 | 35.9 | 35.9 | 35.3 | 36.9 | 36.9 |

Comparison of Residents Who Do and Do Not Receive Restorative Care

The majority of long-stay residents were White females, with a mean age of 85±8 years, residing in urban, for-profit nursing homes for approximately 3.2±3.4 years. Restorative care participants differed significantly from nonparticipants in several baseline characteristics. Participants exhibited greater cognitive impairment (p < .001), a higher number of disabling diseases (p < .001), more physical impairments (p < .001), and greater ADL dependency at baseline (p < .001) (Table 3). Conversely, participants were less likely to be in pain (p = .008), reside in non-profit facilities (p = .02), and their directors of nursing were less likely to have specialty certifications (p = .006).

Table 3. Baseline Comparisons Between Restorative Care Participants and Nonparticipants

| Total sample, N = 7,735 | Received restorative care, N = 1,864 | Did not receive restorative care, N = 5,871 | Chi-square | t | p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Mean ± SD | % | Mean ± SD | % | Mean ± SD | |

| Resident traits | ||||||

| Age in years | 84.8±8.0 | 85.2±8.1 | 84.6±8.0 | |||

| Length of stay in years | 3.2±3.4 | 3.3±3.5 | 3.1±3.3 | |||

| Female | 75.4 | 74.5 | 75.7 | |||

| White race | 88.9 | 89.4 | 88.7 | |||

| Live in urban nursing home | 52.2 | 47.5 | 61.1 | |||

| Live in for profit nursing home | 59.2 | 52.8 | 53.8 | |||

| Cognitive Performance Scale score (range 0–6) | 2.3±1.4 | 2.5±1.3 | 2.2±1.4 | |||

| Frailty (range 0–15) | 6.3±2.2 | 6.2±1.9 | 6.3±2.3 | |||

| Number of disabling diseases (range 0–10) | 2.5±1.4 | 2.8±1.4 | 2.4±1.3 | |||

| Mood scale (range 0–14) | 0.9±1.6 | 1.0±1.7 | 0.9±1.5 | |||

| Social engagement (range 0–6) | 2.5±1.7 | 2.5±1.7 | 2.5±1.6 | |||

| Pain: none | 60.3 | 63.6 | 59.2 | |||

| Pain: mild | 24.0 | 24.0 | 24.0 | |||

| Pain: moderate | 13.7 | 11.4 | 14.4 | |||

| Pain: severe | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.4 | |||

| Number of physical impairments (range 0–4) | 2.7±1.2 | 3.0±1.1 | 2.5±1.2 | |||

| Activities of daily living dependency at baseline (range 0–28) | 15.3±7.6 | 17.5±7.2 | 14.6±7.7 | |||

| Nurse indicated resident had ability to improve ADL dependency | 26.9 | 17.5 | 29.9 | |||

| Nursing home traits | ||||||

| Percentage of residents with Medicare reimbursement | 3.0 | 1 | 3.0 | |||

| Percentage of residents with Medicaid reimbursement | 20.0 | 26 | 18 | |||

| Hours of patient contact with nursing staff | 73.3±110.2 | 70.5±107.1 | 74.2±111.2 | |||

| Medical Director certification | 84.4 | 82.6 | 84.9 | |||

| Director of Nursing certification | 37.3 | 34.6 | 38.2 | |||

| Facility accreditation | 11.1 | 9.4 | 11.7 |

Note: a p value from univariable Chi-square test for categorical variables, and t-test for continuous variables. ADL = Activities of daily living.

Effect of Restorative Care on ADL Dependency

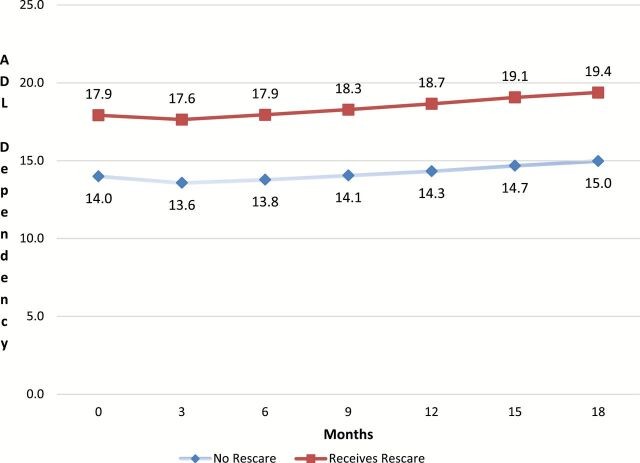

Table 4 presents the multivariable model results. Restorative care programs nursing homes did not demonstrate a significant effect on ADL dependency change (p = .12) after adjusting for resident and nursing home factors. Figure 2 visually represents ADL dependency changes for participants and nonparticipants. After controlling for confounders, the predicted mean baseline ADL dependency score was 17.9 for participants and 14.0 for nonparticipants. Both groups showed statistically similar rates of ADL dependency decline over 18 months, with an increase of 0.5 points for participants and 1.0 point for nonparticipants.

Table 4. Effect of Restorative Care on Change in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Dependency Over 18 Months Controlling for Resident and Nursing Home Confounders

| Characteristic | Coefficient | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.6 | .42 | N/A |

| Resident Traits | |||

| Age in years | .01 | .003 | .15 |

| Length of stay in years | | | .89 | ||

| Cognitive Performance Scale score (range 0–6) | .38 | .03 | <.001 |

| Frailty (range 0–15) | .63 | .01 | <.001 |

| Number of disabling diseases (range 0–10) | .10 | .02 | <.001 |

| Mood scale (range 0–14) | −.16 | .02 | <.001 |

| Social engagement (range 0–6) | −.39 | .02 | <.001 |

| Pain: mild (reference: severe) | −.57 | .20 | .004 |

| Pain: moderate (reference: severe) | −.37 | .20 | .07 |

| Pain: none (reference: severe) | −.55 | .20 | .006 |

| Number of physical impairments (range 0–4) | .97 | .03 | <.001 |

| Activities of daily living baseline score (range 0–28) | .68 | .01 | <.001 |

| Nurse indicated resident did not have the ability to improve ADL dependency | −.13 | .07 | .06 |

| Received any restorative care over time | .09 | .06 | .12 |

| Nursing home traits | |||

| Percentage of residents with Medicare reimbursement | −.07 | .22 | .76 |

| Percentage of residents with Medicaid reimbursement | −.02 | .08 | .75 |

| Hours of patient contact with nursing staff | −.0001 | .0003 | .68 |

| Medical Director has no certification | .19 | .09 | .04 |

| Director of Nursing has no certification | .07 | .07 | .31 |

| Facility has no accreditation | −.11 | .10 | .29 |

Notes: The model included the resident ID to account for repeated records for the same subject. State of nursing home location was included as a random effect. Positive coefficients for continuous variables indicate increasing ADL dependency with predictor value increase. For categorical variables, a positive coefficient indicates increased ADL dependency compared to the reference category.

Predicted change in activities of daily living (ADL) dependency by receipt of restorative care after adjusting for confounding resident and nursing home traits.

Predicted change in activities of daily living (ADL) dependency by receipt of restorative care after adjusting for confounding resident and nursing home traits.

Note: ADL score estimates per month were calculated by applying beta coefficients to covariate values for each subject per quarter, estimating ADL function per subject per quarter. Means were computed for these individual ADL estimates at each time point separately for those who did and did not receive restorative care.

Discussion

While a majority of nursing homes offered Medicare-supported restorative care programs nursing homes, only about one-third of long-stay residents participated. Participants presented with higher ADL dependency, and greater physical and cognitive impairments and comorbidities. However, both participant and nonparticipant groups experienced similar rates of ADL dependency decline, suggesting a broader need for interventions to mitigate functional decline among most long-stay residents.

Baseline restorative care participation was 24%, increasing to 37% over 18 months. This study could not pinpoint reasons for low participation, but prior research suggests resident and organizational factors (Benjamin, Edwards, Ploeg, & Legault, 2014). Residents may perceive activities as unengaging or not beneficial (Benjamin et al., 2014). Staff-reported barriers include limited time to build trust and motivate residents, resident learned dependency, challenges motivating cognitively impaired residents, beliefs about resident inability to participate, efficiency pressures, and fall concerns (Resnick et al., 2008). State reimbursement policies also likely influence participation, as not all Medicaid programs reimburse for restorative care, and 20% of the sample were Medicaid recipients. Only case-mix Medicaid programs currently reimburse for restorative care under Resource Utilization Group criteria. State of residence was included as a random effect to mitigate this confounder.

The most clinically relevant baseline difference was higher ADL dependency in participants (mean ADL score 17.5 vs. 14.6 for nonparticipants). While statistically significant differences in cognitive impairment, comorbidities, and physical impairments were observed due to large sample size, their clinical relevance may be less pronounced. The finding that nurses target residents with higher ADL dependency for restorative care aligns with previous reports (Berg et al., 1997), likely reflecting practice of initiating restorative care when functional impairments become evident. However, the clinically meaningful ADL decline in both groups indicates a widespread need for function maintenance strategies among long-stay residents. An alternative explanation for excluding less dependent residents could be reimbursement structures favoring higher compensation for more dependent residents.

The lack of differential ADL dependency decline between participant and nonparticipant groups suggests that Medicare-reimbursed restorative care programs nursing homes may not achieve their intended effect. This could be related to program intensity and structure. The reimbursed level of 15 minutes per day, six days a week, may be insufficient in frequency and intensity. For example, walking, a common restorative activity, at 15 minutes falls short of the 30 minutes recommended for older adults (Nelson et al., 2007). Program structure was also unknown; whether facilities employed integrated or dedicated approaches is unclear. Dedicated approaches, using specialized staff at specific times, are more likely. Empirical evidence favoring integrated or dedicated approaches is limited. However, a recent review suggests integrated restorative care in controlled settings improves ADL dependency, physical function, walking, and physical activity (Resnick et al., 2013). Another possibility is that higher baseline ADL dependency in participants left less room for improvement, minimizing potential effect. However, a recent randomized trial using an integrative approach showed improved physical function, activity, and reduced falls even in long-stay residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment (Galik et al., 2014), suggesting potential for improvement even in more dependent populations.

These findings should not justify program or reimbursement elimination, as most moderately dependent long-stay residents did not participate in Medicare-supported restorative care programs nursing homes, a group likely to benefit. These results, combined with recent evidence, support the current shift toward implementing restorative care as a philosophy of integrated care rather than discrete activities (Resnick, Galik, & Boltz, 2013). Future research should investigate the effectiveness of expanded restorative care for all long-stay residents and compare integrated versus dedicated program efficacy (Resnick, Galik, Remsburg, & Pretzer-Aboff, 2009).

Limitations

Study limitations warrant consideration. ADL dependency is not the sole outcome for evaluating restorative care. Outcomes specific to each activity type, like gait speed for ambulation programs (Forster, Lambley, & Young, 2010), could provide more precise effect measures but were unavailable in this dataset. MDS restorative care measures could not detect dose-response relationships. Selecting the latest quarterly MDS assessment might bias outcomes towards residents experiencing significant changes, though this bias is minimal (7% of assessments from significant change events). An admission cohort design would be ideal but was infeasible due to the low proportion of newly admitted long-stay residents (<1.5%). Sample attrition at 18 months (40% mortality or discharge) raises uncertainty about how differences between surviving and censored residents impacted ADL dependency progression. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into restorative care participation and effects, guiding future practice and research in restorative care programs nursing homes.

Conclusions

In this nationally representative MDS data sample, two-thirds of nursing homes offered restorative care programs nursing homes, yet less than one-third of long-stay residents participated. Participants had higher ADL dependency but similar progression rates as nonparticipants, suggesting potential benefits for nonparticipants. Implementing restorative care as an integrated philosophy rather than a program of discrete activities is worth considering. Future research should compare integrated and dedicated approaches and assess effectiveness when offered to all long-stay residents to optimize restorative care programs nursing homes.

Funding

This project was supported by Grant Number K12HD055887 from the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program of the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development to the Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health at the University of Minnesota and by grant number 1R03AG037127-01A1 from the National Institute on Aging. Research results and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Census Bureau, the Research Data Center, the National Center for Health Statistics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the National Institutes of Health. K. M. C. Talley was funded by the John A. Hartford Foundation as a Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity pre-doctoral fellow from 2002–2004 and as a Claire M. Fagin post-doctoral fellow from 2008–2010.

Acknowledgements

The research in this article was conducted while the PI (K. M. C. Talley) and statisticians (K. Savik & H. Zhao) were Special Sworn Status researchers of the U.S. Census Bureau at the Minnesota Census Research Data Center. The data for the study was provided by the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This article has been screened to insure that no confidential data are revealed.

References

Armstrong, Stolee, Hirdes, & Poss, 2010

Ang, Au, Yap, & Ee, 2006

Arling, Kane, Mueller, Bershadsky, & Degenholtz, 2007

Benjamin, Edwards, Ploeg, & Legault, 2014

Berg et al., 1997

Burrows, Morris, Simon, Hirdes, & Phillips, 2000

Carpenter, Hastie, Morris, Fries, & Ankri, 2006

Casten, Lawton, Parmelee, & Kleban, 1998

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, n.d.

Center for Disease Control and National Center for Health Statistics, n.d.

Chang, Wung, & Crogan, 2008

Dubeau, Simon, & Morris, 2006

Forster, Lambley, & Young, 2010

Forster et al., 2009

Frederiksen, Tariot, & De Jonghe, 1996

Fried & Guralnik, 1997

Fries, Simon, Morris, Flodstrom, & Bookstein, 2001

Frytak, Kane, Finch, Kane, & Maude-Griffin, 2001

Galik et al., 2008

Galik et al., 2014

Gambassi et al., 1998

Grando et al., 2009

Hartmaier, Sloane, Guess, & Koch, 1994

Hartmaier et al., 1995

Lawton et al., 1998

Lum, Lin, & Kane, 2005

McConnell et al., 2003

Mor, 2004

Mor et al., 1995

Mor, Intrator, Unruh, & Cai, 2011

Morris et al., 1990

Morris et al., 1994

Morris et al., 1999

Nelson et al., 2007

Peres, Verret, Alioum, & Barberger-Gateau, 2005

Reilly, Mueller, & Zimmerman, 2007

Resnick et al., 2006

Resnick et al., 2008

Resnick et al., 2009

Resnick, Galik, & Boltz, 2013

Resnick, Galik, Remsburg, & Pretzer-Aboff, 2009

Reilly, Mueller, & Zimmerman, 2007

Sakari-Rantala, Era, Rantanen, & Heikkinen, 1998

Shin & Scherer, 2009

Snowden et al., 1999

Vahakangas, Noro, & Bjorkgren, 2006

Wang, Kane, Eberly, Virnig, & Chang, 2009

Williams, Li, Fries, & Warren, 1997

Wu, Mor, & Roy, 2009