Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented disruption across various sectors globally, and healthcare is no exception. Urology practices and training programs have been significantly affected, with both immediate and long-term consequences still unfolding. This study delves into the modifications implemented in urology residency programs in the United States in response to the COVID-19 outbreak and examines the perceptions of program leaders and residents regarding the pandemic’s impact on urology trainees.

The US healthcare system faced multifaceted challenges during the pandemic, including shortages of personnel, hospital beds, ventilators, and personal protective equipment, especially in regions overwhelmed with COVID-19 cases. Furthermore, healthcare providers contracting the virus and requiring self-isolation exacerbated the strain. Hospitals in high-prevalence areas resorted to redeployment strategies to address patient care demands. Conversely, regions with lower COVID-19 cases often limited routine patient care to conserve resources, leading to a decline in clinical volume.

Urology, as a surgical subspecialty, traditionally involves a high volume of scheduled surgeries, clinic procedures, and ambulatory visits. COVID-19 severely disrupted this model, with cascading effects on urology trainees concerning surgical and ambulatory experience, educational opportunities, and workforce structures. Beyond these tangible impacts, the pandemic also introduced psychological effects on trainees, ranging from burnout and moral injury to a potential renewed sense of purpose. This study aimed to systematically assess these impacts by surveying program directors (PDs) and residents in US urology residency programs, testing the hypothesis that reduced case volume would correlate with decreased surgical preparedness perception, but potentially an improved sense of morale.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

An anonymous online survey was conducted targeting program leadership (PDs and associate PDs) and residents within accredited urology residency programs in the United States. The American Urological Association (AUA) directory was utilized to identify 142 accredited programs. Contact information for program leadership was gathered from AUA resources and program websites. Surveys were distributed to 127 PDs with a request to share with APDs and residents. Data collection occurred between April 28, 2020, and May 11, 2020, and no responses were excluded. The Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles, determined this study exempt from formal review.

Survey Instrument

The 27-question survey was designed using the Qualtrics platform. The survey questions were developed iteratively with input from faculty and residents. Data collected included respondent demographics (role, program location, gender, training year) and assessed:

- Clinical modifications (surgical and ambulatory practice changes)

- Educational modifications (changes to conferences and learning platforms)

- Workforce restructuring (team sizes, redeployment)

- Perceptions of COVID-19’s impact on training (using a 5-point Likert scale)

The final section aimed to capture the subjective effects of the pandemic on trainees and programs. The complete survey is available as supplemental material.

Data Analysis

Survey responses were analyzed using Stata version 16.1. Responses were coded as binary or categorical variables. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the entire cohort. To analyze geographic impact, a ‘high COVID-19 region’ variable was defined based on the top 10 US states/districts with the highest per-capita COVID-19 infection rates as of May 11, 2020 (New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Washington D.C., Delaware, Louisiana, Illinois, and Maryland). Subgroup analyses comparing high vs. low COVID-19 regions and program leaders vs. residents were performed using Pearson’s chi-square test. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Respondent Demographics

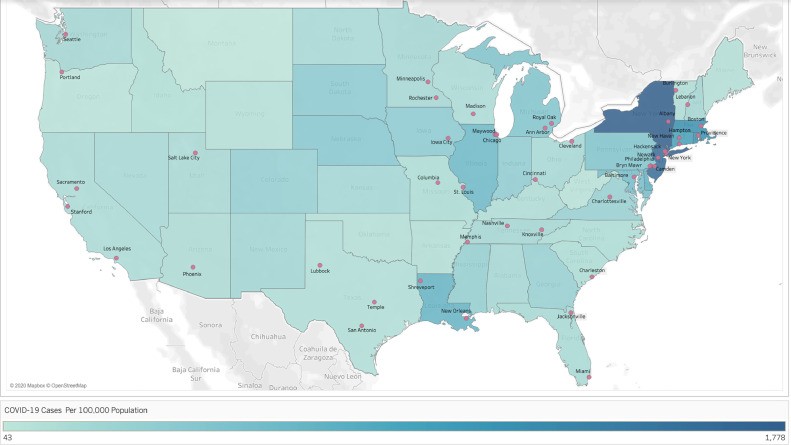

The survey yielded responses from 64 program leaders representing 55 programs (43% response rate) and 106 residents from 23 programs (18% response rate). Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of respondents, with 32% located in high COVID-19 regions. The majority of respondents were male (66%). Among resident respondents, most were junior residents (67% PGY 1-3 vs. 33% PGY 4-6).

Figure 1. Geographic Distribution of Survey Respondents

Survey respondent program locations overlaid on a United States heat map showing COVID-19 per-capita cases by state. Created using Tableau 9.1.

Clinical and Educational Adjustments

Consistent decreases in surgical and ambulatory volumes were reported. Figure 2 shows the decline in surgical case volume across urology subspecialties, including emergency cases. Most residents (93%) continued to assist in ongoing surgeries. Telehealth adoption for ambulatory visits was almost universal (99%), but resident participation was lower (65%), and in-person clinic encounters continued for 51%. In-person educational conferences were almost entirely discontinued (99%), with 95% transitioning to virtual platforms. Interestingly, 54% reported an increase in the number of educational activities overall.

Figure 2. Change in Surgical Volume by Subspecialty

Reported change in surgical volume by urology subspecialty, stratified by total cohort, low COVID-19 region, and high COVID-19 region. Emergency surgical volume showed a significant difference between groups (P = .01).

Workforce Restructuring in Urology Residency Programs

A significant majority (90%) reported reduced resident team sizes for inpatient management. Most residents (83%) were involved in caring for COVID-19 patients. Over half (57%) reported resident stay-at-home periods due to exposure or illness. Modifications were implemented for at-risk trainees: 42% of programs restricted pregnant residents from COVID-19 patient care, and 36% from all direct patient care. Similar modifications were reported for immunocompromised residents. Redeployment of urology residents occurred in 20% of programs, primarily to ICUs (61%) and medical wards (39%). Preparation for redeployment included virtual learning (48%) and in-person procedural instruction (13%). Support services like childcare (60%), temporary housing (75%), and meals (53%) were provided to trainees.

Perceived Impact on Urology Trainees

Table 1 summarizes perceptions regarding the impact of program modifications. A large majority (80%) agreed that surgical training was negatively impacted. Half (51%) expressed increased anxiety about competency upon residency completion. However, only 9% anticipated increased fellowship pursuit. Most respondents acknowledged more time for self-directed learning (90%) and research (77%). Fewer reported improved morale (23%) or increased pride (29%). Home life disruption was noted by 54%, and financial concerns by 39%.

Table 1. Perceived Implications of Urology Training Modifications

| Changes in Urology Services due to COVID-19 Have: | Full Cohort (N=170) Agree (%) | High COVID-19 Region (N=54) Agree (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had a negative impact on surgical training | 79% | 83% | .40 |

| Increased anxiety about competency on residency completion | 51% | 63% | .02 |

| Allowed more time for self-directed learning | 88% | 83% | .35 |

| Allowed more time for research | 76% | 67% | .07 |

| Made me feel more pride in my work | 29% | 24% | .58 |

| Improved morale | 22% | 17% | .14 |

| Increased the likelihood of post-residency fellowship training | 9% | 13% | .14 |

| Disrupted home life | 54% | 57% | .51 |

| Increased financial concerns | 38% | 39% | .99 |

Impact Disparities Between High and Low COVID-19 Regions

Subgroup analysis revealed significant differences between high and low COVID-19 regions. Respondents in high COVID-19 regions more frequently reported decreased emergency urologic surgical volume (76% vs 22%, P = .01), cancelled educational activities (11% vs 1%, P < .05), and resident redeployment (37% vs 11%, P < .05). Anxiety about competency was significantly higher in high COVID-19 regions (63% vs 45%, P = .02). No significant regional difference was found in morale or work pride perceptions.

Program Leader vs. Resident Perceptions

Comparison of program leaders and residents showed agreement across most domains. However, residents were less likely to agree that COVID-19 disrupted home life (31% vs 12% disagreement, P = .013) and less likely to agree about increased financial worries (27% vs 56% agreement, P < .05) compared to program leaders.

Discussion

This national survey provides the first comprehensive assessment of COVID-19 related modifications in US urology residency programs and their perceived impact on trainees. The findings validate the hypothesis that substantial changes occurred across all aspects of surgical training. Consistent with guidelines from urologic and surgical societies, a near-universal decrease in surgeries was reported across subspecialties. Notably, emergency surgical volume also decreased, especially in high COVID-19 regions, potentially reflecting patient reluctance to seek care due to pandemic-related fears. This reduction in surgical volume has significant implications for trainee experience. Unsurprisingly, most respondents agreed that COVID-19 negatively impacted surgical training, raising concerns about meeting Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Urology (ABU) procedural and surgical case standards.

While the long-term duration of reduced case volumes remains unclear, it necessitates attention to resident case logs and potential adjustments to volume-based standards, perhaps supplemented by competency-based evaluations. While short-term volume reductions in high-volume subspecialties may be offset for residents in longer programs, those in shorter subspecialty rotations like pediatric and reconstructive urology risk missing critical exposure. Program leaders should consider flexible scheduling and off-rotation opportunities to compensate for these gaps. The reported increase in time for self-directed learning and research offers a potential avenue to balance lost surgical volume with enhanced educational pursuits, warranting further study into the relative effects of these shifts.

Ambulatory care also saw significant changes, with widespread telehealth implementation. While resident telehealth participation is substantial, maximizing its educational value is crucial, as telehealth is likely to become a permanent component of urologic care. The shift to virtual platforms for conferences and didactics was expected given social distancing recommendations. However, higher cancellation rates in high COVID-19 regions are concerning. Capitalizing on increased time for self-directed learning is paramount to mitigate decreased operative experience. Medical educators have long explored innovative strategies like flipped classrooms and virtual lecture libraries, and the pandemic has accelerated the adoption of these methods, providing broader access to high-quality educational resources.

Workforce restructuring was evident, including smaller inpatient teams and resident redeployment, particularly in high COVID-19 regions, mirroring trends in other surgical specialties. Managing resident absences and protecting vulnerable trainees, especially pregnant residents, required program adjustments. While modifications for pregnant residents were common, higher rates of unmodified duties in high COVID-19 regions may reflect critical staffing needs. Program leaders should consider telehealth roles for such trainees where feasible.

Perceptions of training impact revealed widespread agreement on negative effects on surgical training and increased anxiety about competency, especially in high COVID-19 regions. This aligns with the greater training disruptions in these areas. However, the lack of significant difference in morale and pride between regions was unexpected, suggesting resident resilience or delayed psychological impacts. Home life disruption was commonly reported, despite available support services, reflecting concerns for family well-being, consistent with findings in general surgery. Residents appeared less financially concerned than program leaders, likely due to the stability of their fixed salaries.

Limitations of this study include potential response bias and over-representation from heavily impacted regions. Defining high COVID-19 regions at the state level may not capture local variations in infection density, although residency programs’ location in population centers mitigates this somewhat. While program representation was strong, lower resident response rates may limit the detection of individual psychosocial impacts.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has triggered significant modifications in US urology residency programs, including reduced clinical volumes, increased telehealth, virtual education, and workforce restructuring. Both program leaders and trainees perceive a negative impact on surgical training and heightened anxiety about competency. Collaboration between program leaders and trainees is crucial to address these challenges and develop solutions for the ongoing and future impacts of the pandemic on urology training.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.051.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

(References from the original article should be listed here if possible. Due to constraints, they are omitted in this example for brevity but should be included in a complete rewrite.)