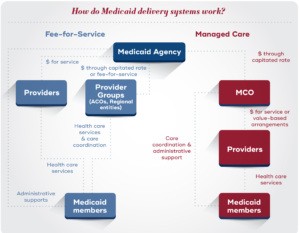

Medicaid stands as a cornerstone of the U.S. healthcare system, providing health coverage to nearly 90 million individuals as of August 2023. Far from being solely a safety net for the impoverished, Medicaid’s scope is extensive, encompassing low-income families, children with intricate health needs, expectant mothers, senior citizens, individuals with disabilities, and low-income adults. Similar to other insurance providers, Medicaid agencies don’t directly deliver healthcare. They are tasked with establishing a “delivery system” to reimburse healthcare providers for services rendered to Medicaid beneficiaries. The healthcare delivery landscape primarily features two models: fee-for-service, where the Medicaid agency directly compensates providers, and capitated managed care, where an external Managed Care Organization (MCO) is paid by the agency to manage provider payments. Presently, a vast majority of states utilize capitated managed care for at least a portion of their Medicaid benefits, with around 72% of Medicaid recipients enrolled in comprehensive managed care in 2021. This shift raises a crucial question: is a managed care program good for Medicaid and its beneficiaries?

Within the comprehensive capitated managed care framework, the state or territory provides the MCO with a fixed monthly payment, known as a capitation rate, for each Medicaid member enrolled in their plan. In return for this “per member per month” payment, the MCO assumes responsibility for numerous functions. These include building a network of healthcare providers, processing payments to these providers for covered services utilized by enrollees, implementing utilization management protocols like prior authorization, and actively engaging with enrollees to coordinate their care. These responsibilities are meticulously outlined in the contractual agreement between the MCO and the Medicaid agency. While the capitation rate is designed to cover member needs, managed care operates as a risk-based model. An MCO could face financial losses if service costs and administrative expenses surpass the capitation rate. Conversely, they can generate profit if these costs remain below the monthly payment.

In contrast, under a fee-for-service model, the Medicaid agency typically manages these functions internally, directly paying healthcare providers for each service delivered to Medicaid members. However, in recent years, many states have adopted strategies to introduce care management elements into fee-for-service systems. This includes establishing Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and regional entities. Within these innovative models, provider groups collaborate to coordinate patient care and may assume financial risk for the health outcomes of a defined patient population.

Federal regulations mandate that comprehensive managed care contracts must encompass a broad spectrum of medical benefits. However, states and territories retain the option to “carve out” specific benefits, such as behavioral health, dental, or pharmacy services, into separate limited benefit plans or retain them within the fee-for-service system. They can also tailor plans to specific demographic groups, for example, creating specialized plans for foster care youth or managed long-term services and supports. The significant flexibility granted to states and territories in designing their delivery systems leads to considerable variation across Medicaid agencies. This variation is evident in the number of managed care plans offered, the percentage of Medicaid members enrolled in managed care, and the specific benefits delivered through managed care arrangements.

The Rise of Managed Care in Medicaid: A Historical Perspective

As of July 2022, 41 states had implemented some form of comprehensive managed care in their Medicaid programs, accounting for over half of total Medicaid expenditure. How did managed care become the dominant model for delivering Medicaid benefits?

While prepaid health plans have roots dating back to the early 20th century, the modern concept of Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) gained momentum with the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973. This landmark legislation established federal standards for HMOs, allocated federal funding to pilot HMOs as an alternative to traditional fee-for-service models, and mandated that employers offer HMO coverage options. The HMO Amendments of 1976 introduced the “50/50” rule, stipulating that Medicaid agencies could only contract with federally qualified HMOs if no more than 50% of their enrollees were Medicaid or Medicare beneficiaries. This provision served as a safeguard against potential fraud and misleading marketing practices by MCOs. The threshold was subsequently raised to 75% in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 and ultimately eliminated by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, paving the way for the widespread expansion of Medicaid managed care.

Over time, Congress also enacted regulations governing the interactions between Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations. Section 1932 of the Social Security Act establishes crucial guidelines for Medicaid managed care plan operations, encompassing aspects like freedom of coverage choice, enrollment procedures, member notifications, consumer protections, and provider network adequacy. Furthermore, Section 1932 mandates Medicaid agencies to undertake specific oversight responsibilities for managed care plans, including developing a quality assessment and improvement strategy and facilitating annual external quality reviews.

In response to this evolving federal framework, numerous states and territories have transitioned towards managed care delivery models. As explored further below, various factors have driven this increasing interest in managed care, including the pursuit of budget predictability, leveraging enhanced federal flexibilities, and the potential for improved coordination of patient care. However, important questions remain regarding the actual impact of managed care on healthcare quality and access for Medicaid beneficiaries.

State and Territorial Decisions: Weighing Delivery System Options

Why might a state or territory opt for managed care to deliver Medicaid services over a traditional fee-for-service model? The decision to adopt or abandon managed care has significant implications for both state budgets and the delivery of healthcare services. Consequently, state legislatures and governors are invariably involved in decisions concerning delivery system models, with Medicaid agencies often implementing managed care at the direction of state legislative bodies.

Proponents of managed care frequently highlight potential advantages in terms of enhanced access to care and improved healthcare quality. However, it’s important to note that academic research on the outcomes associated with managed care models presents a mixed picture. While some studies suggest improvements in quality and access under managed care, others have found no significant impact or even worse outcomes compared to fee-for-service. Furthermore, ongoing debate persists regarding whether MCOs are optimally positioned to deliver effective care coordination or if provider-led entities like ACOs are more effective in this role.

Key Operational Components of Managed Care Programs

Effectively implementing and managing a Medicaid managed care program involves several core operational components:

Procurement

Medicaid agencies enter into contracts with managed care organizations to deliver specific healthcare benefits and services to Medicaid recipients. These contracts, typically spanning three to five years, have a profound impact on the healthcare experiences of millions of Medicaid beneficiaries and can represent billions of dollars in state expenditure. Given the high stakes involved, Medicaid agencies have developed rigorous procurement processes to ensure they select MCOs capable of delivering high-quality care.

Most states employ a competitive procurement process to select MCO partners. This process typically involves the state issuing a Request for Proposals (RFP) outlining specific requirements and inviting interested MCOs to submit bids. The state or territory then undertakes a thorough evaluation process to score these proposals and award the managed care contract. The number of MCOs contracted varies across states; in 2019, some states contracted with only one MCO, while others had as many as 25.

States and territories utilize the procurement process to articulate their goals for the Medicaid delivery system and identify health plan partners who can effectively contribute to achieving those goals. For instance, a Medicaid agency might incorporate specific contract requirements, such as mandating new covered services, quality improvement initiatives, or member engagement strategies, aligned with their broader program objectives. The agency might also incorporate specific questions, scenario-based assessments, scoring frameworks, and requests for historical performance data (e.g., HEDIS metrics, records of corrective action plans) to assess which MCO is best equipped to support the agency’s strategic priorities, such as enhancing healthcare quality, promoting value-based purchasing, or integrating care for individuals dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. Ultimately, the MCO contracts resulting from this procurement process fundamentally shape the healthcare experiences of Medicaid beneficiaries, determining the services they can access, the providers they can see, and the overall administration of their care.

Key Stages of a Procurement Process

The complete procurement cycle typically spans 18-24 months, encompassing pre-planning, the active bidding phase, and contract implementation. This process involves several distinct stages:

- Information Gathering for Vision and Goal Definition: A Medicaid agency’s overarching vision for its healthcare delivery system is the driving force behind the managed care procurement process. Defining this vision necessitates input from key stakeholders, including Medicaid beneficiaries, healthcare providers, and community-based organizations. Gathering this information through town hall meetings, requests for information, and stakeholder consultations can take several months.

- Translating Vision into a Request for Proposals (RFP): The state or territory must then translate its defined vision and goals into a formal RFP document. The RFP outlines contract requirements, oversight mechanisms, and requests detailed information on the MCO’s proposed programs and operational capabilities. Interested health plans then submit “bids” in response to these RFPs.

- Establishing Procedural Standards to Mitigate Protests: Formal protests against procurement decisions can consume significant state resources and cause delays in managed care implementation. Medicaid agencies often collaborate with legal counsel to develop strategies for minimizing the risk of formal protests, including implementing standardized evaluation processes.

- Proposal Scoring and Contract Award: Upon receiving proposals from interested MCOs, the state or territory evaluates the bids against pre-determined criteria. Many Medicaid agencies utilize formal scoring rubrics to ensure a fair and standardized evaluation process. Contracts are awarded based on the outcomes of these evaluations.

- Contract Execution, Readiness Review, and Implementation: After selecting an MCO, the state or territory must translate the selected plan’s proposal into a legally binding contract that codifies the specific benefits and services the plan will provide. Subsequently, the Medicaid agency and the MCO transition to the implementation phase, which involves establishing necessary systems and reporting structures to ensure the MCO fulfills its contractual obligations, aligning IT systems to facilitate member enrollment, and conducting readiness reviews. Readiness reviews, typically conducted several months before the plan’s “go-live” date, are crucial for ensuring a smooth and successful implementation.

Rate Setting

Under capitated managed care, Medicaid agencies compensate MCOs using a “per member per month” payment model. In exchange for this capitation rate, the MCO provides the contracted services and administrative functions. This arrangement effectively transfers the financial risk associated with unpredictable healthcare costs from the Medicaid agency to the MCO. Annually, each Medicaid agency, in conjunction with its actuarial experts, must develop these capitation rates and obtain certification from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Federal regulations mandate that these rates be actuarially sound, defined as rates that are “projected to provide for all reasonable, appropriate, and attainable costs” required by the contract for the specified period and covered population. Medicaid agencies and their actuaries must also adhere to specific regulatory requirements governing the development and documentation of their rate-setting methodologies.

Predicting the actual cost of healthcare services in a given year is inherently complex. Unforeseen fluctuations in service utilization by Medicaid members or the emergence of new, high-cost treatments (like GLP-1 drugs for diabetes and weight loss) can significantly impact healthcare expenditures. To mitigate the financial risks associated with setting rates that are either too high or too low, Medicaid agencies can employ fiscal tools such as medical loss ratios and risk corridors. Medical loss ratios (MLRs) represent the proportion of total capitation revenue that a plan spends on direct healthcare services and quality improvement activities, as opposed to administrative expenses, profit, or advertising. If a plan’s MLR falls below a specified threshold, the state can require the plan to refund a portion of its revenue. Similarly, risk corridors enable Medicaid agencies and MCOs to share savings or losses that exceed pre-defined thresholds outlined in the contract.

Oversight

Robust oversight is a critical component of the relationship between Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations. MCOs, like any organization, operate with their own set of incentives and stakeholders, including profit targets, investors, and corporate boards. Effective oversight mechanisms are essential to ensure that MCOs operate in alignment with Medicaid agencies’ overarching goals of promoting access to care and ensuring high-quality healthcare for beneficiaries.

Oversight processes are typically embedded within the contractual agreements between Medicaid agencies and their managed care plans. These contracts explicitly define how Medicaid agencies expect MCOs to deliver services and outline enforcement mechanisms to be invoked if MCOs fail to meet these contractual expectations. Medicaid agencies continuously monitor various data points, including access standards (e.g., provider network adequacy, appointment wait times), member and provider complaints and grievances, and encounter data, to identify areas where MCOs may be falling short of contract compliance. The federal government also mandates specific oversight responsibilities for states and territories in their management of managed care plans. Medicaid agencies are required to develop an annually updated quality strategy, complete the Managed Care Program Annual Report (MCPAR) which includes quality metrics and grievance and appeal data, and arrange for annual quality reviews conducted by external organizations.

Medicaid agencies employ a range of penalties and incentives to ensure MCO compliance with contract terms. If an MCO is found to be non-compliant, the state may implement formal enforcement actions, such as corrective action plans, financial penalties, and enrollment restrictions. Many Medicaid agencies also utilize strategies like withholding a portion of the capitation rate unless the plan achieves specific quality targets, publicly reporting data on plan performance, and establishing financial or enrollment-based incentives to encourage desired outcomes. Collectively, these oversight strategies empower Medicaid agencies to ensure that their contracted managed care organizations are delivering high-quality, accessible care to Medicaid beneficiaries.

The Evolving Landscape of Medicaid Managed Care

Medicaid managed care has experienced substantial growth over the past two decades, with over 70% of Medicaid beneficiaries currently enrolled in MCOs. How might managed care continue to evolve in the future?

Firstly, Medicaid agencies’ priorities and choices regarding delivery systems are constantly shifting. In recent years, some agencies have chosen to carve out services like behavioral health and pharmacy benefits into managed care or revert them back to fee-for-service. Many states have also explored targeted managed care plans tailored to specific patient populations, such as former foster care youth or individuals with intellectual disabilities. Notably, managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) have experienced significant growth, with expenditure increasing from $6.7 billion in FY2008 to $47.5 billion in FY2019. Furthermore, Medicaid programs are increasingly looking to their managed care plans to address health-related social needs and reduce disparities in healthcare access and outcomes. These evolving priorities have tangible impacts on how, where, and what type of care Medicaid beneficiaries receive.

Market dynamics are also poised to shape the future of managed care. The managed care market has witnessed a wave of consolidation in recent years; currently, five major managed care companies account for 50% of national Medicaid MCO enrollment. While research on the specific impacts of managed care consolidation in Medicaid is limited, studies from other insurance markets suggest that consolidation can influence healthcare prices, quality of care, patient access, provider compensation, and overall healthcare spending.

Finally, the regulatory landscape governing managed care continues to evolve. In April 2023, CMS issued a proposed rule on Medicaid managed care. This proposed rule would introduce significant new requirements for both Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations, encompassing enhanced access standards, more rigorous quality assessments, and refined payment analyses. It also proposes modifications to fiscal tools like state-directed payments and in lieu of services arrangements. Separately, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General has initiated investigations focusing on prior authorization and other utilization management practices within Medicaid managed care. At the state level, there has been a surge of innovation in managed care oversight strategies, including increased emphasis on strategies to mitigate health disparities. Collectively, these regulatory and policy shifts indicate a growing focus on ensuring that MCOs deliver accessible, high-quality care to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Medicaid delivery systems are inherently complex, exhibiting significant variation across states and territories, patient populations, and service categories. The choices Medicaid agencies make regarding delivery systems, particularly the utilization of capitated managed care, have a tangible impact on the healthcare experiences of Medicaid beneficiaries. As Medicaid managed care continues to evolve, rigorously evaluating its impact on healthcare quality, access, and cost will be crucial to determine if a managed care program is indeed good for Medicaid and the millions it serves.

This resource was developed with support from The Commonwealth Fund.